A brief history of CSS until 2016

The CSS saga

The saga of CSS starts in 1994. Håkon Wium Lie works at CERN – the cradle of the Web – and the Web is starting to be used as a platform for electronic publishing. One crucial part of a publishing platform is missing, however: There is no way to style documents. For example, there is no way to describe a newspaper-like layout in a Web page. Having worked on personalized newspaper presentations at the MIT Media Laboratory, Håkon saw the need for a style sheet language for the Web.

Style sheets in browsers were not an entirely new idea. The

separation of document structure from the document's layout had

been a goal of HTML from its inception in 1990. Tim Berners-Lee

wrote his NeXT browser/editor in such a way that he could

determine the style with a simple style sheet. However, he didn't

publish the syntax for the style sheets, considering it a matter

for each browser to decide how to best display pages to its users.

In 1992, Pei Wei developed a browser called Viola,

which

had its own style sheet language.

However, the browsers that followed offered their users fewer and fewer options to influence the style. In 1993, NCSA Mosaic, the browser that made the Web popular, came out. Stylewise, however, it was a backward step because it only allowed its users to change certain colors and fonts.

Meanwhile, writers of Web pages complained that they didn't have enough influence over how their pages looked. One of the first questions from an author new to the Web was how to change fonts and colors of elements. At that time, HTML did not provide this functionality – and rightfully so. This excerpt from a message sent to the www-talk mailing list early in 1994 gives a sense of the tensions between authors and implementors:

In fact, it has been a constant source of delight for me over the past year to get to continually tell hordes (literally) of people who want to -- strap yourselves in, here it comes -- control what their documents look like in ways that would be trivial in TeX, Microsoft Word, and every other common text processing environment: "Sorry, you're screwed."

The author of the message was Marc Andreessen, one of the programmers behind NCSA Mosaic. He later became a co-founder of Netscape, a company eager to fulfill the request of authors. On October 13, 1994, Marc Andreessen announced to www-talk that the first beta release of Mozilla (which later turned into Netscape Navigator) was available for testing. Among the new tags the new browser supported was center, and more tags were to follow shortly.

Three days before Netscape announced the availability of its new

browser, Håkon published the first draft of the

Cascading HTML Style Sheets proposal. Behind the scenes,

Dave Raggett (the main architect of HTML 3.0) had encouraged the

release of the draft to go out before the upcoming Mosaic and

the Web

conference in Chicago. Dave had realized that HTML

would and should never turn into a page-description language and

that a more purpose-built mechanism was needed to satisfy

requirements from authors. Although the first version of the

document was immature, it provided a useful basis for discussion.

Among the people who responded to the first draft of CSS was Bert Bos. At that time, he was building Argo, a highly customizable browser with style sheets, and he decided to join forces with Håkon. Both of the two proposals look different from present-day CSS, but it is not hard to recognize the original concepts.

One of the features of the Argo style language was that it was

general enough to apply to other markup languages in addition to

HTML. This also became a design goal in CSS and HTML

was

soon removed from the title of the specification. Argo also had

other advanced features that didn't make it into CSS1, in

particular, attribute selectors and generated text. Both features

had to wait for CSS2.

Cascading Style Sheets

wasn't the only proposed style

language at the time. There was Pei Wei's language from the Viola

browser, and around 10 other proposals for style sheet languages

were sent to the www-talk and www-html mailing

lists. Then, there was DSSSL, a complex style and transformation

language under development at ISO for printing SGML documents.

DSSSL could conceivably be applied to HTML as well. But, CSS had

one feature that distinguished it from all the others: It took

into account that on the Web, the style of a document couldn't be

designed by either the author or the reader on their own, but that

their wishes had to be combined, or cascaded,

in some way;

and, in fact, not just the reader's and the author's wishes, but

also the capabilities of the display device and the browser.

As planned, the initial CSS proposal was presented at the Web

conference in Chicago in November 1994. The presentation at

Developer's Day caused much discussion. First, the concept of a

balance between author and user preferences was novel. A

fictitious screen shot showed a slider with the label user

on one side and author

on the other. By adjusting the

slider, the user could change the mix of his own preferences and

those of the author. Second, CSS was perceived by some as being

too simple for the task it was designed for. They argued that to

style documents, the power of a full programming language was

needed. CSS went in the exact opposite direction by making a point

out of being a simple, declarative format.

At the next WWW conference in April 1995, CSS was presented

again. Both Bert and Håkon were there (in fact, this was the

first time they met in person) and this time, they could also show

implementations. Bert presented the support for style sheets in

Argo, and Håkon showed a version of the Arena browser that

had been modified to support CSS. Arena had been written by Dave

Raggett as a testbed for new ideas, and one of them was style

sheets. What started out as technical presentations ended up in

political discussions about the author-reader balance.

Representatives from the author

side argued that the author

ultimately had to be in charge of deciding how documents were

presented. For example, it was argued that there may be legal

requirements on how warning labels had to be printed and the user

should not be able to reduce the font size for such warnings. The

other side, where Bert and Håkon belong, argued that the

user, whose eyes and ears ultimately have to decode the

presentation, should be given the last word when conflicts

arise.

Outside of the political battles, the technical work continued. The www-style mailing list was created in May 1995, and the discussions there have often influenced the development of the CSS specifications. Almost 10 years later, there were more than 16,000 messages in the archives of the mailing list. And after 20 years, more than 80,000!

In 1995, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) also became operational. Companies were joining the Consortium at a high rate and the organization became established. Workshops on various topics were found to be a successful way for W3C members and staff to meet and discuss future technical development. It was therefore decided that another workshop should be organized, this time with style sheets as the topic. The W3C technical staff working on style sheets (namely Håkon and Bert) were now located in Sophia-Antipolis in Southern France where W3C had set up its European site. Southern France is not the worst place to lure workshop participants to, but because many of the potential participants were in the U.S., it was decided to hold the workshop in Paris, which is better served by international flights. The workshop was also an experiment to see if it was possible for W3C to organize events outside the U.S. Indeed, this turned out to be possible, and the workshop was a milestone in ensuring style sheets their rightful place on the Web. Among the participants was Thomas Reardon of Microsoft, who pledged support for CSS in upcoming versions of Internet Explorer.

At the end of 1995, W3C set up the HTML Editorial Review Board (HTML ERB) to ratify future HTML specifications. Because style sheets were within the sphere of interest of the members of the new group, the CSS specification was taken up as a work item with the goal of making it into a W3C Recommendation. Among the members of the HTML ERB was Lou Montulli of Netscape. After Microsoft signaled that it was adding CSS support in its browser, it was also important to get Netscape on board. Otherwise, we could see the Web diverge in different directions with browsers supporting different specifications. The battles within the HTML ERB were long and hard, but CSS level 1 finally emerged as a W3C Recommendation in December 1996.

In February 1997, CSS got its own working group inside W3C and the new group set out to work on the features which CSS1 didn't address. The group was chaired by Chris Lilley, a Scotsman recruited to W3C from the University of Manchester. CSS level 2 became a Recommendation in May 1998. Since then, the group has worked in parallel on new CSS modules and errata for CSS 2.

The W3C working group has members (around 15 in 1999, around 115

in 2016) who are delegated by the companies and organizations

that are members of W3C. They come from all over the world, so the

meetings

are usually over the phone, and last about an hour

every week. About four times each year, they meet somewhere in the

world.

Browsers

The CSS saga is not complete without a section on browsers. Had it not been for the browsers, CSS would have remained a lofty proposal of only academic interest. The first commercial browser to support CSS was Microsoft's Internet Explorer 3, which was released in August 1996. At that point, the CSS1 specification had not yet become a W3C Recommendation and discussions within the HTML ERB were to result in changes that Microsoft developers, led by Chris Wilson, could not foresee. IE3 reliably supports most of the color, background, font, and text properties, but it does not implement much of the box model.

The next browser to announce support for CSS was Netscape Navigator, version 4.0. Since its inception, Netscape had been skeptical toward style sheets, and the company's first implementation turned out to be a half-hearted attempt to stop Microsoft from claiming to be more standards-compliant than Netscape. The Netscape implementation supports a broad range of features – for example, floating elements – but the Netscape developers did not have time to fully test all the features that are supposedly supported. The result is that many CSS properties cannot be used in Navigator 4.

Netscape implemented CSS internally by translating CSS rules into snippets of JavaScript, which were then run along with other scripts. The company also decided to let developers write JSSS, thereby bypassing CSS entirely. If JSSS had been successful, the Web would have had one more style sheet than necessary. This, fortunately for CSS, turned out not to be the case.

Meanwhile, Microsoft continued its efforts to replace Netscape

from the throne of reigning browsers. In Internet Explorer 4,

the browser display engine, which among other things is

responsible for rendering CSS, was replaced by a module code-named

Trident.

Trident removed many of the limitations in IE3,

but also came with its own set of limitations and bugs. Microsoft

was put under pressure by the Web Standards Project (WaSP), which

published IE's Top 10 CSS Problems

in November 1998 (see

Figure 1).

![[image]](history-wasp.png)

Subsequent versions of Internet Explorer have considerably improved the support for CSS.

small-screen renderingtransforms pages into columns.

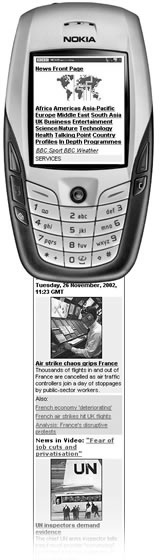

The third browser that ventured into CSS was Opera. The browser

from the small Norwegian company made headlines in 1998 by being

tiny (it fit on a floppy!) and customizable while supporting most

features found in the larger offerings from Microsoft and

Netscape. Opera 3.5 was released in November 1998, and

supported most of CSS1. The Opera developers (namely Geir

Ivarsøy) also found time to test the CSS implementation

before shipping, which is a novelty in this business. Håkon,

was so impressed with Opera's technology that he joined the

company as CTO in 1999. One important market for Opera's browser

is mobile phones. By reformatting pages to fit on a small screen

(@media is handy here), the Web has been

freed from the desktop (see Figure 2).

The people at Netscape responded to the increasing competition

with a move that was novel at the time: They released the source

code for the browser. With the source code public, anyone could

inspect the internals of their product, improve it, and make

competing browsers based on in. Much of the code, including the

CSS implementation, was terminated shortly after the release, and

the Mozilla

project was formed to build a new generation

browser. CSS was in important specification to handle and

countless hours have been spent by volunteers to make sure pages

are displayed according to the specification. Several browsers

have been based on the Mozilla code, including Galeon and Firefox.

Apple is often seen as a technology pioneer, but for a long

time, it did not spend much resources on Web browsers. Apple left

it to Microsoft to build a browser for its machines, and Internet

Explorer for Mac actually had better support for CSS than the

Windows version of the browser. In 2003, Microsoft discontinued

support for the Mac and Apple announced a new browser called

Safari.

Safari isn't entirely new – it is based on

the open source Konqueror browser, which was developed for the KDE

system running on Linux.

For Web designers, it is good news to have several competing products based on Web standards. Although some efforts to test that your pages display well in all browsers are necessary, the fact that Web pages can be displayed on a wide range of machines is a huge improvement from the past:

Anyone who slaps a

this page is best viewed with Browser Xlabel on a Web page appears to be yearning for the bad old days, before the Web, when you had very little chance of reading a document written on another computer, another word processor, or another network.

– Tim Berners-Lee in Technology Review, July 1996

Beyond browsers

The CSS saga isn't only about Web browsers. Many people outside of the few that program Web browsers have made important contributions to CSS over the past years.

The CSS1 test suite was a landmark development for CSS

and W3C.

When the first two CSS implementations came out and could be

compared, we realized there was a problem. You could not expect

the style sheet tested only in one browser to work in the other

browser. To rectify the situation, Eric Meyer – with help

from countless other volunteers – developed a test suite

that implementors would test against while there still was time to

fix the problems. Todd Fahrner created the acid

test in

October 1998, which

became the ultimate challenge. See Figure 3.

![[Several colored boxes next and above each other]](sec5526c.gif)

When a test suite is available, someone must do the testing. Brian Wilson has done a remarkable job of testing CSS implementations and making the results available on the Web.

We should also mention the work in more recent years of Gérard Talbot and Geoffrey Sneddon on the official CSS testuite. And of course of Peter Linss, whose Shepherd server is a great help in seeing what tests exist, running them, and generating reports of results.

Without compelling content, CSS hasn't served its purpose. Dave Shea created the CSS Zen garden to show fellow graphics artists why CSS should be taken seriously. He, along with the many people who created submissions, showed people how to use CSS creatively.

The Web has been trapped on the desktop for too long. Making it available on mobile phones is one important escape. Michael Day and Xuehong Liu have shown us another way out: The Prince formatter converts HTML and XML documents to PDF and is entirely based on CSS. This product enabled Håkon and Bert to abandon traditional word processors and use Web standards. Their book was written entirely in HTML and CSS.

Web Fonts

CSS level 2 contained a feature called Web Fonts

,

i.e., the ability to embed fonts in a Web document. The idea was

that a designer who wanted a specific font could actually provide

the font along with the style sheet. During ten years, only

Microsoft's Internet Explorer browser implemented that feature.

(Netscape for a short period implemented an alternative, which

didn't use CSS, wasn't as good, and was probably illegal in many

countries because it slightly changed how each font looked.)

The reason Web Fonts didn't get implemented was twofold. First of all there were few fonts whose copyright allowed them to be distributed. Most fonts could be used to print documents locally, but you weren't allowed to put them on the Web.

Secondly, Microsoft and Monotype had developed a format called EOT (Embedded OpenType), which contained inside the fonts the names (URLs) of the documents that could be rendered with them. This allowed an EOT font to be made available on the Web alongside a document, because it now couldn't be used for any other document. But, the format was proprietary and nobody else but Microsoft could use it.

All that changed in early 2008. By then there were many more free fonts, i.e., fonts whose designers allowed them to be distributed for free on the Web. Håkon therefore started lobbying browser makers to finally implement Web Fonts (for fonts in the standard TrueType and OpenType formats) and Bert asked Microsoft if they couldn't open up EOT, so that others could implement it, too. In May, Microsoft and Monotype submitted EOT to W3C under a royalty-free license. And browsers started implementing support for downloading TrueType and OpenType fonts.

After further discussion, however, most browser makers decided not to implement EOT, but ask W3C to develop a new font format instead. The reason was that that they preferred to use the gzip compression algorithm (which was already used for HTTP) rather than add new code for the MicroType Express algorithm used by EOT.

That new format became WOFF.

Rather than embed the URL of a document in the font, it relies on

an HTTP feature (the origin

header), which allows to give

the domain part of a document's URL: less precise than a full URL,

but still good enough for most font makers.

In the end, however, WOFF still adopted parts of EOT's MicroType Express algorithm, and a new compression algorithm (Brotli), because it allowed better compression than gzip.

Web Fonts have become very popular. Free fonts are used directly in the TrueType or OpenType format in which they were made. Less free fonts use the WOFF and EOT formats.

There are now online services where you can find and download fonts (both free and non-free). And some even offer to host the fonts on their servers. In some cases even for free. (Which means they provide bandwidth, but in return they gather statistics on font usage).

New directions: books and GUIs

The development of CSS hasn't stopped. Far from it. CSS now has more than 60 modules that define different capabilities, some already part of the standard, some still in development.

It is now common that books are made with CSS. Not all books, though, because CSS is still missing features for the more complex layouts. That is one direction in which the language is being extended.

E-books also use CSS, which requires yet other features. EPUB is the most widely implemented format for e-books. It was developed by IDPF. IDPF and W3C are currently (December 2016) in the process of merging their operations. The next EPUB version should then be made at W3C and the development of CSS features for books and e-books will be easier.

The development of programs (apps

) that use graphical

user interfaces made out of HTML and CSS has also put new demands

on CSS. Some of the latest modules of CSS deal with layout of user

interfaces rather than documents. Although: as they are part of

the same CSS, nothing prohibits their use for documents, too, if a

part of a document happens to have a mark-up structure that allows

it.

Over time, some browsers and other implementations have disappeared, and new ones have been created. There are now also languages derived from CSS for other purposes than styling documents. Probably the first language that used the syntax of CSS (but not the cascading and inheritance model) was STTS, by Daniel Glazman. That was in 1998. Since then others have made their appearance. Three that are currently in use are Qt Style Sheets for styling widgets in the Qt GUI toolkit, JavaFX Style Sheets, which does the same for the JavaFX UI widgets of Java, and MapCSS for describing the style of maps.

It is difficult to count how widely CSS is used, but the number of HTML pages that does not use CSS is probably not more than a few percent. Many people make their living as CSS designers or from CSS conferences. And the number of books written about CSS can no longer be counted.

Some day CSS will be replaced by something else. But before that, CSS will have time to celebrate its 21st birthday…