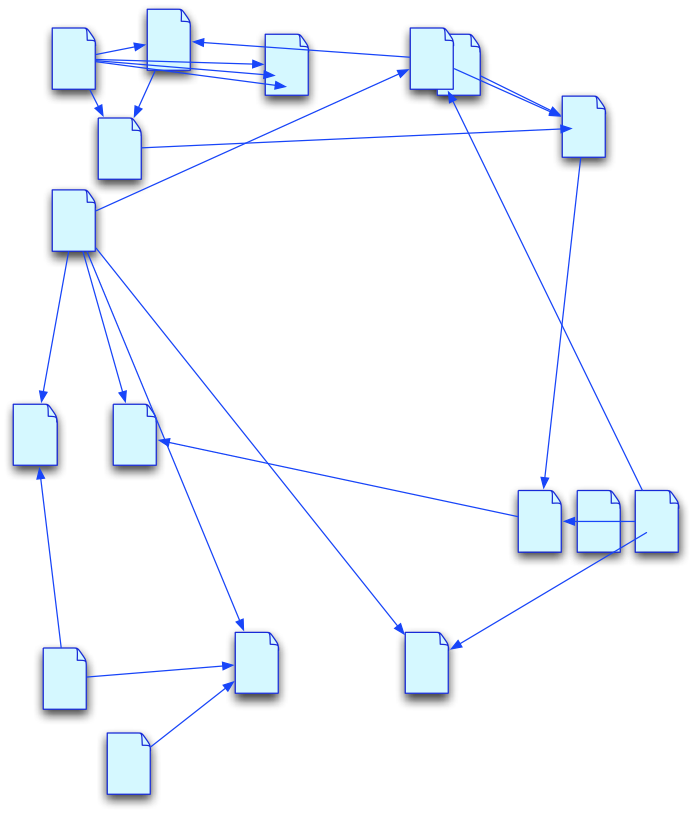

Progress in communications technology has ben characterizsed by a movement from lower to higher levels of abstraction.

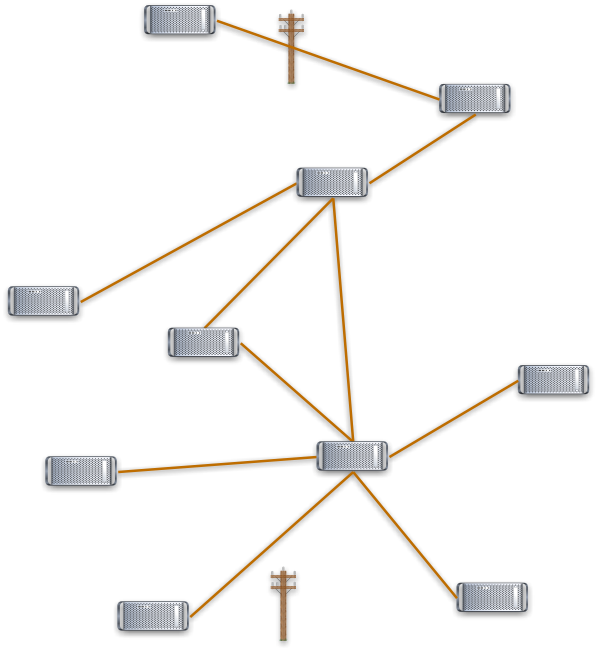

When, first, computers were connected by telephone wires, then you would have to run a special program to make one connect to another. Then you could make the second connect to a third, but you had to know how to use the second one. Mail and news would be passed around by computters calling each other late at night. Email addresses for a while contained a list of computers to pass the message through (timbl@mcvax!cernvax!cernvms)

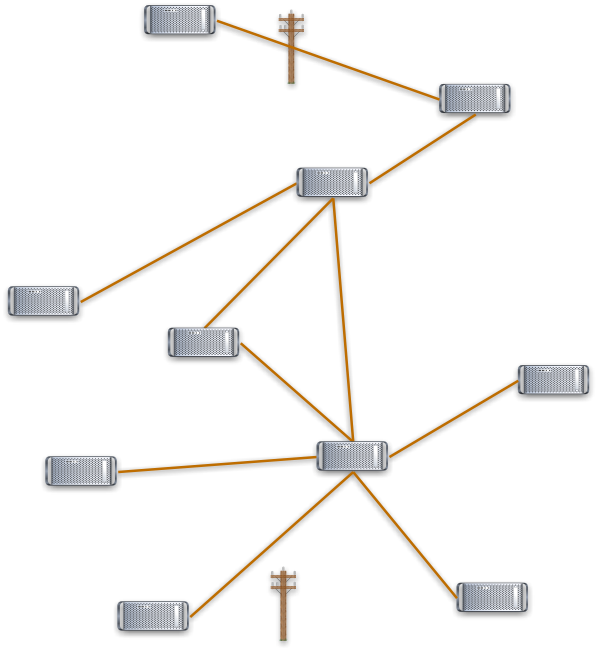

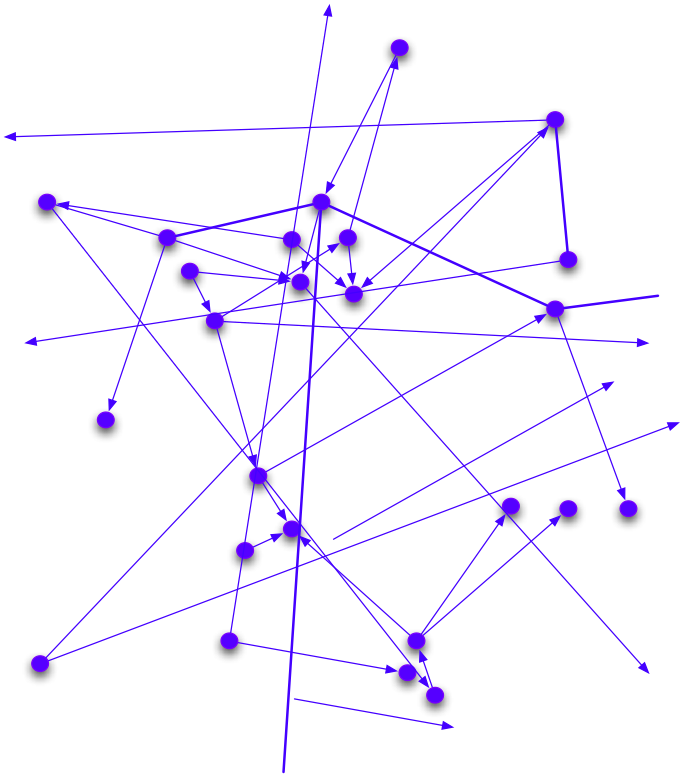

The ability to use this communication power between computers wasn't powerfully useful until the Internet. The internet allowed one to forget about the individual connections. It was thought of as the "Internet Cloud". Messages went in and appeared ad another computer, without (when things worked) one having to worry about how they were broken into packets, and the packets routed from computer to computer. The Domain Name System gives computers names, and the TCP and IP protocols allows a program on one computer to talk to a program on another computer.

This made life very much easier. It takes the wires out of the picture, and allows the programs to talk as though the computers were directly connected.

Of course, when things went wrong, one did have to do run diagnostic programs to find out whether the connection has broken between one's own computer and the WiFi base unit, or between that and the router, the cable modem, or somewhere in the middle of the Internet, or at the other end. But that was the exception.

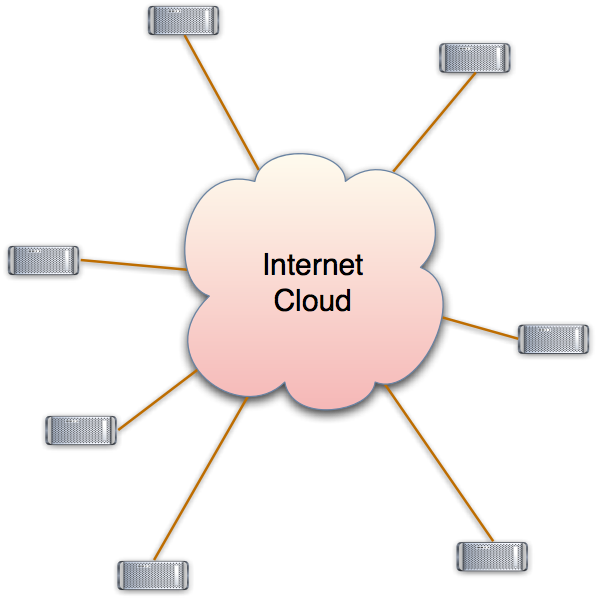

This power of communication between computers wasn't really easily usable by normal people until the Web came along. The realization of the web is: "It's not the computers which are interesting, it is the documents!" The WWW protocols (URI, HTTP, HTML) defined how documents could be sent between Web servers and Web browsers.

Now the user is apparently in a web of interconnected documents. She does not have to worry about how the protocols work underneath, with two exceptions.

When things go wrong, she has to be able to figure out whether it as a problem with her connection to the internet, with the URI in the link she was following, or an error on the server end. This involves looking under the hood. But that is the exception.

There is another reason to be aware of what is happening. The information you are browsing comes from a particular server, whose name has registered against a particular person or organization. The trust you put in that information is related to who that organization is. It is the serving organization which is responsible for keeping the URIs you bookmark today alive tomorrow -- and some are better at it than others. Phishing attacks succeed when people are fooled into thinking it is an organiztion you trust when it isn't.

So the web is just a web of documents, except one one has to lift the hood for debugging or questions of trust.

Note that the connection between the net of computers and the web of documents is clear in the URI:

http://acme.excample.com/products/machin/truc

_________________

The computer owner name (acme.example.com) is part of the name of the document. The Acme Example company is responsible for supporting the document on the web.

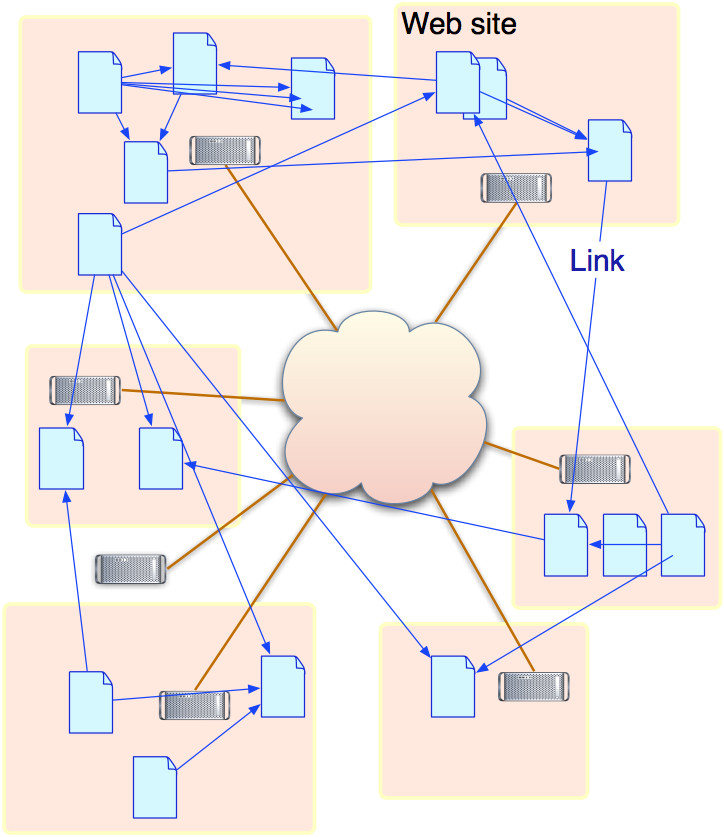

The power of the web was still not totally used to its full potential until the semantic web came along. The Semantic Web's realization is: It is isn't the documents which are actually interesting, it is the things they are about!

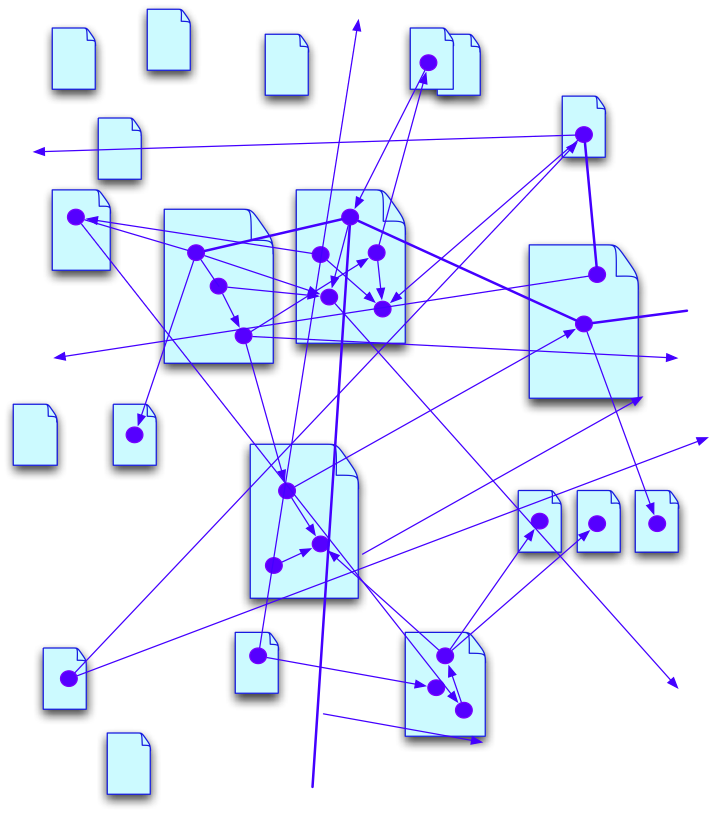

A person who is interested in a web page on something is usually primarily interested in the thing rather than the document. There are exceptions, of course -- documents are certainly interesting in their own right. However, when it comes to the business and science, the customers, the products, or the proteins and the genes, are the things of interest. A good Semantic Web browser, then, shows a user information about the thing, which may have been merged from many sources. Primarily, the user is aware of the abstract web of connections between the things -- this person is a customer who made this order which includes this item which is manufactured by this facility ... and so on.

There are again the same two exceptions. When things go wrong, the user must be able to look under the hood to see whether the document was fetched OK but had missing data, or the document was not fetched OK, in which case what was the underlying web problem.

And again, when the user is looking at a bit of data in the data view, perhaps a point on a map or a cell in a table, then she must be able to see easily which document that information came from.

Note that the connection between the web of documents and the web of things is clear in the URI:

http://acme.excample.com/products/machin/truc#part3

_____________________________________________

The name of the document is part of the name of the thing. A

given thing may have many URIs of course. But when URIS have this

form, it is clear that we are talking about a thing as described by

a given document. This is a gene as defined in the Gene Ontology.

This is a protein as defined in this taxonomy. A citizen as defined

by the Immigration and Naturalization Service glossary. And so on.

(There are (since 2005) URIS for things which are not explicitly bound to a document. These require the server to respond with the name of a suitable document at runtime. This is more complicated)

The web of things is built on the web of documents, which is built on the web of computers controlled by Domain Name owners, which itself is build on a set of interconnected cables. This is an architecture which provides a social backing to the names for things. It allows people to find out the social aspects of the things they are dealing with, such as provenance, trust, persistence, licensing and appropriate use as well as the raw data. It allows people to figure out what has gone wrong when things don't work, by making the responsibility clear.

The value of this architecture is that each layer leverages the social components of the lower layer's architecture.