This specification provides guidelines for designing Web content authoring

tools that are more accessible for people with disabilities.

An authoring tool that conforms to these guidelines will promote accessibility

by providing an accessible user interface to authors with disabilities

as well as enabling, supporting, and promoting the production of accessible

Web content by all authors.

"Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines 2.0" (ATAG 2.0) is part

of a series of accessibility guidelines published by the W3C Web Accessibility Initiative

(WAI).

You are reading the Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) version 2.0. This document includes recommendations for assisting authoring tool developers to make their tools (and the Web content that the tools generate) more accessible to all people, especially people with disabilities, who may potentially be either authors or end users. These guidelines have been written to address the requirements of many different audiences, including, but not limited to: policy makers, technical administrators, and those who develop or manage content. An attempt has been made to make this document as readable and usable as possible for that diverse audience, while still retaining the accuracy and clarity needed in a technical specification.

ATAG 2.0 is part of a series of accessibility guidelines published by the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI). The relationship between these documents is explained in "Essential Components of Web Accessibility" [COMPONENTS].

This document consists of:

-

this introduction;

- information about conformance;

- the guidelines with normative success criteria. (Note: The checkpoints in this section are numbered differently than the content in other sections. For example, "Checkpoint A.1.2" refers to the second

checkpoint of the first guideline in the first part of the guidelines);

- links to a separate non-normative document, entitled "Techniques for Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines 2.0" [ATAG20-TECHS] (the "Techniques document" from here on), that provide sufficient and advisory techniques for how each success criteria might be satisfied, (Note: These techniques are informative examples only, and other strategies may be used or required to satisfy the checkpoints);

- references and a glossary;

- appendices containing a checklist and a document comparing the checkpoints in ATAG 1.0 to those in this document (ATAG 2.0).

1.1 Definition of authoring

tool

ATAG 2.0 defines an "authoring tool" as: any software, or collection

of software components, that authors use to create or modify Web content for publication, where

a "collection of software components" are any software products used together (e.g., base

tool and plug-in) or separately (e.g., markup editor, image editor, and

validation tool), regardless of whether there has been any formal collaboration

between the developers of the products.

The following categories are an informative illustration of the range of tools covered by ATAG 2.0. The categories are

used primarily in the Techniques document [ATAG20-TECHS]

to mark examples that may be of interest to developers of particular types

of tools. Note: Many authoring tools include authoring

functions from more than one category (e.g., an HTML

editor with both code-level and WYSIWYG editing views):

-

Code-level Authoring Functions: Authors have full control

over all aspects of the resulting Web content that have bearing on the

final outcome. This covers, but is not limited to plain text editing,

as this category also covers the manipulation of symbolic representations

that are sufficiently fine-grained to allow the author the same freedom

of control as plain text editing (e.g., graphical tag placeholders).

Examples: text editors, text editors enhanced with graphical

tags, some wikis, etc.

-

-

Object Oriented Authoring Functions: Authors have control

over functional abstractions of

the low level aspects of the resulting Web content.

Examples: timelines, waveforms, vector-based graphic editors, objects which represent web implementations for graphical widgets (e.g., menu widgets) etc.

Indirect Authoring Functions: Authors have control over

only high-level parameters related to the automated production of the

resulting Web content. This may include interfaces that assist the author

to create and organize Web content without the author having control over

the markup, structure, or programming implementation.

Examples: content management systems, site building wizards, site

management tools, courseware, blogging tools, content aggregators, conversion

tools, model-based authoring tools, etc.

The guiding principle of ATAG 2.0 is that:

Everyone should have the ability to create and access Web content.

Authoring tools play a crucial role in achieving this principle because the

accessibility of the tool's authoring tool user interface determines

who can access the tool as a Web content author and

the accessibility of the resulting Web content determines who can be an end user of that Web content.

The approach taken to the production of accessible content in these guidelines is one of enabling, supporting, and guiding the author. In general, the Working Group does not believe that enforcing particular author behavior through overly restrictive mechanisms is a workable solution.

As an introduction to accessible authoring tool design, consider that the

authors and end users of Web content may be using the tool and its output in

contexts that are very different from that which may be regarded as typical.

For example, authors and end users may:

- not be able to see, hear, move, or be able to process some types

of information easily or at all;

- have difficulty reading or comprehending text;

- not have or be able to use a keyboard or mouse;

- have a text-only display, or a small screen.

For more information, see "How People with Disabilities Use the Web"

[PWD-USE-WEB]. In addition, following the guidelines provides benefits for authors

and end users beyond those listed in these various disability-related

contexts. For example, a person may have average hearing, but still require

captions for audio information due to a noisy workplace.

Similarly, a person working in an eyes-busy environment may require an audio

alternative to information they cannot view.

1.3 Relationship

to the Web Content

Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)

This section is normative.

At the time of publication, version 1.0 of WCAG is a W3C Recommendation [WCAG10], and a second version of the guidelines is under development [WCAG20]. Note that the two versions have somewhat different Conformance Models.

ATAG 2.0 refers to WCAG as a benchmark for

judging the accessibility of Web content (see the term "Accessible Web Content") and Web-based authoring tool user interfaces (see the term "Accessible Authoring Tool User Interface"). For more information on how WCAG acts as a benchmark, see "Relative Priority" Checkpoints.

Note that the references to WCAG in the guidelines section of ATAG 2.0 are made without an associated version number. This has been done to

allow developers to select, and record in the conformance profile,

whichever version of WCAG is most appropriate for the circumstances of a given

authoring tool. The Working Group does recommend considering the following factors

when deciding which WCAG version to use:

- The latest version of WCAG will be the most accurate with respect to state-of-the-art

technologies and accessibility best practices. Older versions of WCAG may

include requirements that are no longer necessary, due to advances in user

agent technology.

- The versions of WCAG differ with respect to the formats for which there

are published WCAG technique documents. This is important because ATAG 2.0

requires published content type-specific WCAG benchmark documents, which may be based on WCAG technique documents, if they are available.

- The versions of WCAG differ in the degree to which they match the legislation

and policies that drive author requirements. Many authors will be seeking

to use authoring tools to create Web content that meets legislation, corporate

policies, etc. It is likely that as WCAG progresses, so too will legislation

and policies, albeit at an uneven pace. Authoring tool developers may, therefore,

consider supporting both versions of WCAG.

2. Conformance

This section is normative.

2.1 Conformance Model

Conformance Levels

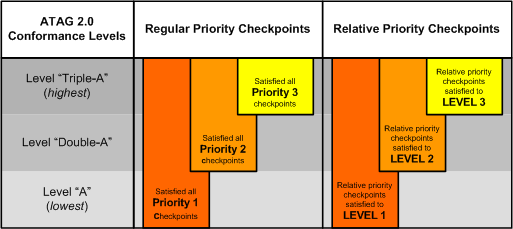

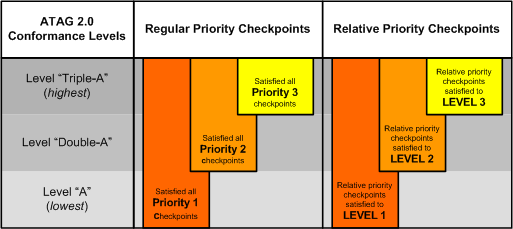

Authoring tools may claim conformance to ATAG 2.0 at one of

three conformance levels. The level achieved depends on the priority of those checkpoints for which the authoring tool has satisfied the success criteria. The levels are:

- Level "A"

- The authoring tool has satisfied all Priority 1 "regular priority" checkpoints and has also satisfied all of the "relative priority" checkpoints to at least Level 1.

- Level "Double-A"

- The authoring tool has satisfied all Priority 1 and Priority 2 "regular priority" checkpoints and has also satisfied all of the "relative priority checkpoints" to at least Level 2.

- Level "Triple-A"

- The authoring tool has satisfied all "regular priority" checkpoints and has also satisfied all of the "relative priority checkpoints" to Level 3.

Figure 1: A graphical view of the requirements

of the ATAG 2.0 conformance level "ladder".

The graphic is a table with four rows and three columns. The header row labels are "ATAG 2.0 Conformance Levels", "Regular Priority Checkpoints" and "Relative Priority Checkpoints". The data rows are labeled Level 'Triple-A' (highest), Level 'Double-A', and Level 'A' (lowest). Bars superimposed across the rows demonstrate that in order to meet each higher level, additional regular priority checkpoints must be met as well as increasing levels of relative priority checkpoints.

Checkpoint Priorities

Each checkpoint has been assigned a priority

level that indicates its importance and determines whether that checkpoint must be met in order

for an authoring tool to achieve a particular conformance

level. There are three

levels of "regular priority" checkpoints as

well as a special class of "relative priority"

checkpoints that rely on WCAG to determine their importance.

"Regular Priority" Checkpoints:

- Priority 1

- Significance in Part A: If the authoring

tool does not satisfy these checkpoints, one or more groups of authors

with disabilities will find it impossible to author

for the Web using the tool.

Significance in Part B: These checkpoints are

essential to helping all authors to

create Web content that conforms to WCAG.

- Priority 2

- Significance in Part A: If the authoring tool does not satisfy these checkpoints,

one or more groups of authors with disabilities will find it difficult to

author for the Web using the tool.

Significance in Part B: These checkpoints

are

important to helping all authors create Web content that conforms to WCAG.

- Priority 3

-

- Significance in Part A: If the authoring tool does not satisfy these checkpoints,

one or more groups of authors with disabilities will find it inefficient to

author for the Web using the tool.

Significance in Part B: These

checkpoints are

beneficial to helping all authors to create Web content that conforms to WCAG.

The

importance of each "relative priority" checkpoint depends on the requirements of whichever version of WCAG the evaluator has chosen to specify in the conformance

profile.

These checkpoints can be met at one of three levels:

- Relative Priority - Level

1

-

- Significance in Part A (checkpoint A.0.1 only): The

user interface checkpoint has been satisfied at a minimal

conformance level (i.e., level A) to WCAG (version 1.0 or 2.0)

as specified in the conformance profile (including

content type-specific WCAG benchmark document).

Significance in Part B: The Web content production checkpoint

has been satisfied at a minimal conformance level (i.e., level

A) to WCAG (version 1.0 or 2.0) as specified in the conformance

profile (including content type-specific WCAG

benchmark document).

- Relative Priority - Level

2

- Significance in Part A (checkpoint A.0.1 only):

The user interface checkpoint has been satisfied at an intermediate

conformance level (i.e., level Double-A) to WCAG (version 1.0 or

2.0) as specified in the conformance profile

(including content type-specific WCAG benchmark document)

Significance in Part B: The Web content production checkpoint

has been satisfied at an intermediate conformance level

(i.e., level Double-A) to WCAG (version 1.0 or 2.0) as specified

in the conformance profile (including content

type-specific WCAG benchmark document)

- Relative Priority - Level

3

- Significance in Part A (checkpoint A.0.1 only):

The user interface checkpoint has been satisfied at a stringent

conformance level (i.e., level Triple-A) to WCAG (version 1.0 or

2.0) as specified in the conformance profile

(including content type-specific WCAG benchmark document)

Significance in Part B: The Web content production checkpoint

has been satisfied at a stringent conformance level (i.e., level

Triple-A) to WCAG (version 1.0 or 2.0) as specified in

the conformance profile (including content

type-specific WCAG benchmark document)

Relative Priority Checkpoints in Practice:

If an authoring tool developer intends to claim conformance to ATAG 2.0 at Level-A, they will first identify, in the conformance claim, a published content type-specific WCAG benchmark document that is targeted at WCAG conformance Level-A (i.e., the requirements in the benchmark are those required to conform to Level-A of WCAG).

Then, for each Relative Priority checkpoint in ATAG 2.0, this document will be used as a benchmark for determining whether the success criteria have been met. For instance, Checkpoint B.2.2 ("Check for and inform the author of accessibility problems") is a Relative Priority checkpoint. To conform to ATAG 2.0 at Level-A, this checkpoint must be met at Relative Priority - Level 1. To do this, the authoring tool must satisfy the success criteria of the checkpoint with respect to all of the requirements in the benchmark document. An example of this can be seen in the first success criteria ("An individual check must be associated with each requirement in the content type-specific WCAG benchmark document...").

2.2 Conformance Claims

A conformance claim is an assertion by a claimant that

an authoring tool

has satisfied the requirements of a chosen ATAG 2.0 conformance

profile.

Conditions

- At least one version of the conformance claim must be published on the Web as a document that conforms to either WCAG (version 1.0 or 2.0) Level A [WCAG10] or WCAG 2.0 Level Single-A [WCAG20]. A suggested metadata description for this document is "ATAG 2.0 Conformance Claim".

- Whenever the claimed conformance level is published (e.g., in marketing materials), the URI for the on-line published version of the conformance claim must be included in conjunction with that claim.

- The existence of a conformance

claim does not imply that the W3C has reviewed the claim or assured its validity.

As of the publication of this document, W3C does not act as an assuring party,

but it may do so in the future, or it may establish recommendations for assuring

parties.

- Claimants may be anyone (e.g., developers, journalists, other third

parties).

- Claimants are solely responsible for the accuracy of their claims and keeping

claims up to date.

- Claimants are encouraged to claim conformance to the most recent version

of the Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines Recommendation that is available.

Components of an ATAG 2.0 Conformance Claim

- Required: The date of the claim.

- Required: The name of the authoring tool and sufficient additional information, as required, to specify the version (e.g., vendor name, version number, minor release number, required patches or updates, natural language of the user interface or documentation). The version information may refer to a range of tools (e.g., "this claim refers to version 6.x"). Note: If the authoring tool is comprised of more than one component (e.g., a markup editor, an image editor, and a validation tool), then this information must be provided separately for each component, although the conformance claim will treat them as a whole.

-

Required: A conformance profile, which must include the following:

- (a) The conformance level that has been satisfied (choose one of: "A", "Double-A", "Triple-A").

- (b) A list of all of the content type(s) produced by the authoring tool. When content types are typically produced together (e.g., HTML and JavaScript, various compound document combinations), they can be listed separately or together as one content type item. For each content type, indicate

whether it is either:

- (i) covered by the conformance claim. For each of these content type items, the URI of a content type-specific WCAG benchmark document must be provided. Only the authoring of "covered" content type(s) is relevant when determining if the checkpoint success criteria have been met. At least one content type must be "covered" in order for a conformance claim to be valid.

- (ii) not covered by the conformance claim. The authoring of "uncovered" content type(s) is not relevant when determining if the checkpoint success criteria have been met

- (c) For authoring tools with Web-based functionality:

- (i) The version and URI of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines document that the user interface was evaluated against. It is optional to provide a content type-specific WCAG benchmark document for each content types used in the implementation of the user interface.

- (ii)The name and version information of the user agent(s) on which the Web-based functionality was evaluated for conformance.

- (d) For authoring tools with functionality that is not Web-based:

- (i) The name and version information of the operating system platform(s) on which the authoring tool was evaluated for conformance.

- (ii) The name and version of the accessibility platform architectures employed.

- Required: A description of how the normative success criteria were met for each of the checkpoints that are required for the conformance level specified by the conformance profile. For relative priority checkpoints this means describing how the requirements of the content type-specific WCAG benchmark document are satisfied.

- Optional: A description of the authoring tool that identifies the types of authoring tool functions that are present in the tool. Choose one or more of: (a) Code-level authoring functions, (b) WYSIWYG authoring functions, (c) object oriented authoring functions, and (d) indirect authoring functions.

- Optional: Any additional information about the tool, including progress towards the next conformance level.

Content Type-Specific

WCAG Benchmark

The purpose of the Content Type-Specific WCAG Benchmark document (the "Benchmark" from here on) is to ensure that the authoring tool is consistent with respect to production of accessible content. For example, if the checking function detects a problem, the repair function must be able to help the author fix it. In practical terms, the Benchmark document is just the WCAG Techniques document when one exists for a content type. However, when a WCAG Techniques document does not already exist for a content type, the claimant may publish their own Benchmark document. The Benchmark has the following characteristics:

- All of the requirements in the Benchmark become normative for a particular Conformance Claim by the act of including a reference to the URI of the Benchmark in the Conformance Profile.

- The Benchmark can be created by any person or organization (although the Working Group does suggest checking to see if a Benchmark has already been published by the W3C or other provider for a content type, before creating a new one).

- The Benchmark must be published on the Web (the URI will appear in the conformance profile) where it will be open to public and market scrutiny.

Each Benchmark document must include the following:

- The name and version of the content type(s) covered by the document (e.g., plain "HTML 4.01" or "HTML 4.01 and CSS 1.0" or "SVG 1.0 and PNG images") and optionally the URI of the specification(s). The version may be a defined range, but may not be open-ended range.

- The version and URI of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines and/or Techniques document(s) used as a basis for the Benchmark (e.g., "Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0 Working Draft, http://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG20/").

- A target WCAG conformance level

(e.g., single-"A",

double-"A", or triple-"A") that the creator

of the Benchmark is claiming that Web content would conform to, if all of

the Benchmark requirements are met. If the tool allows the author to choose

between different WCAG levels, then each level needs its own Benchmark document.

- For

each success criteria in WCAG that is required by the target WCAG conformance

level (this is set in point 3 of the Conformance Claim), the Benchmark must provide either at least one

requirement for meeting the success criteria or an explanation of why that

success criteria is not applicable to the content type in question.

The Working Group

suggests the following resources are relevant when creating a Benchmark document:

- For WCAG 1.0: WCAG 1.0 guidelines [WCAG10], "Techniques for WCAG 1.0" [WCAG10-TECHS], and the W3C access note series (published for CSS 2.0 [CSS2-ACCESS], SVG [SVG-ACCESS], and SMIL [SMIL-ACCESS]).

- For WCAG 2.0: WCAG 2.0 guidelines [WCAG20], "General

Techniques for WCAG 2.0" [WCAG20-TECHS-GENERAL], technology-specific techniques for WCAG 2.0 (WCAG-GL is developing technology-specific WCAG 2.0 techniques for HTML [WCAG20-TECHS-HTML], CSS [WCAG20-TECHS-CSS], and client-side scripting [WCAG20-TECHS-SCRIPTING]), and the W3C access note series (published for CSS 2.0 [CSS2-ACCESS], SVG [SVG-ACCESS], and SMIL [SMIL-ACCESS]), and Understanding WCAG 2.0 [WCAG20-UNDERSTANDING].

2.3 "Progress Towards Conformance" Statement

Developers of authoring tools that do not yet conform fully to a particular ATAG 2.0 conformance level are encouraged to publish a statement on progress towards conformance. This statement would be the same as a conformance claim except that this statement would specify an ATAG 2.0 conformance level that is being progressed towards, rather than one already satisfied, and report the progress on success criteria not yet met. The author of a "Progress Towards Conformance" Statement is solely responsible for the accuracy of their statement. Developers are encouraged to provide expected timelines for meeting outstanding success criteria within the Statement.

3. The Authoring Tool Accessibility

Guidelines

This section is normative.

How the guidelines are organized

The guidelines are divided into two parts, each reflecting a key aspect of accessible authoring tools. Part A includes guidelines and associated checkpoints related to ensuring accessibility of the authoring tool user interface. Part B contains guidelines and checkpoints related to ensuring support for creation of accessible Web content by the tool. The guidelines in both parts include the following:

- The guideline number.

- The guideline title.

- An explanation of the guideline.

- A list of checkpoints for the guideline.

Each checkpoint listed under a guideline is intended to be specific enough to be verifiable, while still allowing developers the freedom to meet the checkpoint in a way that is suitable for their own authoring tools. Each checkpoint definition includes the following parts. Some parts are normative (i.e., relate to conformance), while others are informative only:

PART A: Make the authoring tool user interface accessible

The checkpoints in Part A are intended to increase the accessibility of

the authoring experience for authors with disabilities. For this reason,

the requirements are narrowly focused on the accessibility of the user

interface that the author uses to operate the tool. The

accessibility of the Web content produced is addressed in Part B.

Note for tools with previews: The requirement in this section apply to all parts of the authoring tool user interface except for the content view of any built-in preview features (see Checkpoint A.2.9 for requirements on previews). In general, the configuration of the preview mode is not defined by the configuration of the editing views.

PART B: Support the production of accessible content

The checkpoints in Part B are intended to increase the accessibility of

the Web content produced by any author to end users with

disabilities. While the requirements in this part do not deal with the

accessibility of the authoring tool user interface, it should be noted

that any of the features (e.g., checker, tutorial) added to meet Part B must also meet the user

interface accessibility requirements of Part A.

GUIDELINE

B.1: Enable the production of accessible content

The creation of accessible content is dependent on the actions of the tool

and the author. This guideline delineates the responsibilities that rest

exclusively with the tool.

- B.1.1 Support content types that enable the creation of content that conforms to WCAG.

[Priority 1]

-

Rationale: Content types with

published content type-specific WCAG benchmark documents facilitate

the creation of Web content that can be

assessed for accessibility with WCAG.

Techniques: Implementation Techniques for Checkpoint B.1.1

- B.1.2 Ensure that the authoring tool preserves accessibility information during

transformations and conversions. [Priority

1]

-

Rationale: Accessibility information is critical to maintaining comparable levels of accessibility across transformations and conversions.

Techniques: Implementation Techniques for Checkpoint

B.1.2

- B.1.3

Ensure that the author is notified before content is automatically removed. [Priority

2]

-

Rationale: Automatically removing markup can cause the unintentional loss of structural information. Even unrecognized

markup may have accessibility value, since it may include recent technologies that have

been added to enhance accessibility.

Techniques: Implementation Techniques for Checkpoint

B.1.3

Success Criteria:

- The authoring tool must provide an option to notify the author before permanently removing content using an automatic process.

- B.1.4

Ensure that when the authoring tool automatically generates content it conforms

to WCAG. [Relative Priority]

-

Rationale: Authoring tools that automatically generate

content that does not conform

to WCAG are a

source of accessibility

problems.

Note: If accessibility information is required from the author during the automatic generation process, Checkpoint B.2.1 applies.

Techniques: Implementation Techniques for

Checkpoint B.1.4

- B.1.5

Ensure that all pre-authored content for the authoring tool conforms to WCAG. [Relative Priority]

-

Rationale: Pre-authored content, such as templates,

images, and videos, is often included with authoring tools for use

by the author. When this content conforms

to WCAG,

it is more convenient for authors and more easily reused.

Note: If accessibility information is required from the author during use, Checkpoint B.2.1 applies.

Techniques: Implementation Techniques for

Checkpoint B.1.5

Success Criteria:

- Any content (e.g.,

templates, clip art, example pages, graphical widgets) that is bundled with

the authoring tool or preferentially licensed to the users of the

authoring tool (i.e., provided for free or sold at a discount) must conform to WCAG when

used by the author.

GUIDELINE B.2: Support

the author in the production of accessible content

Actions may be taken at the author's initiative that may result in accessibility

problems. The authoring tool should include features that provide support

and guidance to the author in these situations, so that accessible

authoring practices can be followed and accessible

web content can be produced.

- B.2.1 Prompt and assist the author to create content that conforms to WCAG.

[Relative Priority]

-

Rationale: The authoring tool should help to prevent

the author from making decisions or omissions that cause accessibility

problems. If Web content accessibility problems are prevented, less effort is required

to create content that conforms

to WCAG. Different

tool developers will accomplish this goal in ways that are appropriate

to their products, processes, and authors.

Techniques: Implementation Techniques for Checkpoint

B.2.1

Success Criteria:

- The authoring tool must provide an option to notify the author when content is added or updated, that requires accessibility

information from

the author to conform to WCAG (e.g., using a dialog box, using interactive feedback).

- Instructions provided to the author by the authoring tool must (if followed) meet one of the following:

- B.2.2 Check for and inform the author of accessibility problems. [Relative Priority]

-

Rationale: Authors may not notice or be able to check for accessibility

problems without assistance from the authoring

tool.

Note: While automated checking and more advanced implementations of semi-automated checking may improve the authoring experience, this is not required to meet the success criteria for this checkpoint.

Techniques: Implementation Techniques for Checkpoint

B.2.2

Success Criteria:

- An individual check must be associated with each requirement in the content type-specific WCAG benchmark document (i.e., not blanket statements such as "does the content meet all the requirements").

- For checks that are associated with a type of element (e.g.,

img), each element instance must be individually identified as potential accessibility problems. For checks that are relevant across multiple elements (e.g., consistent navigation) or apply to most or all elements (e.g., background color contrast, reading level), the entire span of elements must be identified as potential accessibility problems, up to the entire content if applicable.

- If the authoring tool relies on author judgment to determine if a potential accessibility problem is correctly identified, then the message to the author must be tailored to that potential accessibility problem (i.e., to that requirement in the context of that element or span of elements).

- The authoring tool must present checking as an option to the author at or before the completion of authoring.

Note: This checkpoint does not apply to authoring

tools that constrain authoring choice to such a degree that it is not

possible to create content that does not conform to WCAG.

- B.2.3

Assist authors in repairing accessibility problems. [Relative Priority]

-

Rationale: Assistance by the authoring tool may

simplify the task of repairing accessibility

problems for some authors, and make

it possible for others.

Note: While automated repair and semi-automated repair may improve the authoring experience, providing repair instructions is sufficient to meet the success criteria for this checkpoint.

Techniques: Implementation Techniques for

Checkpoint B.2.3

- B.2.4 Assist authors to ensure that equivalent alternatives for non-text objects are accurate and fit the context. [Priority 1]

-

Rationale: Improperly generated equivalent alternatives can create accessibility problems and interfere with accessibility checking.

Techniques: Implementation Techniques for Checkpoint B.2.4

Success Criteria:

- If the authoring tool offers text alternatives for non-text objects, then the source of the alternatives for each object must be at least one of the following:

(Text alternatives should not be generated from unreliable sources. File names are generally not acceptable, although in some cases they will be (e.g., if they store alternatives previously entered by authors))

- The authoring tool must allow the author to accept, modify, or reject equivalent alternatives.

- B.2.5 Provide functionality for managing, editing, and reusing equivalent alternatives. [Priority 3]

-

Rationale: Simplifying the initial production and

later reuse of equivalent alternatives will encourage authors to use

them more frequently. In addition, such an alternative equivalent management

system will facilitate meeting the requirements of Checkpoints B.2.1,

B.2.2, B.2.3 and B.2.4.

Techniques: Implementation Techniques for Checkpoint B.2.5

- B.2.6 Provide the author with a summary of accessibility status. [Priority 3]

-

Rationale: This summary will help authors to improve the accessibility status

of their work, keep track of problems, and monitor progress.

Techniques: Implementation Techniques for Checkpoint B.2.6

- B.2.7

Provide the author with a tutorial on the process of accessible authoring. [Priority

3]

-

Rationale: Authors are more likely to use features

that promote accessibility, if they understand when and how to use them.

Techniques: Implementation Techniques for Checkpoint B.2.7

Success Criteria:

- The authoring tool must provide a tutorial on the accessible authoring process that is specific to the tool.

4. Glossary

This glossary is normative. Some definitions may differ from those in other WAI documents. The definitions here serve the goals of this Recommendation.

- accessibility

problem, authoring tool user interface

- An authoring tool user interface accessibility problem is an aspect of

an authoring tool user interface

that fails to meet one of the checkpoint success criteria in Part

A. The severity of a given problem is reflected in the priority of the

checkpoint.

- accessibility

problem, Web content

- A Web content accessibility problem is an aspect of Web

content that fails to meet some requirement of WCAG.

The severity of a given problem is relative and is determined by reference

to WCAG.

- accessible

Web content

- Web content (e.g., output of an authoring

tool) that conforms to WCAG.

- accessible

authoring tool user interface

- For Web-based functionality, this is an authoring tool user interface

that conforms to WCAG. For non-Web-based

functionality this is an authoring tool user interface that meets the success

criteria in Part A. The severity of

a given problem is reflected in the priority of the checkpoints.

- accessibility

information

- Accessibility information is the information that is necessary and sufficient

for undertaking an accessible authoring

practice. For a particular content type,

this information may include, but is not limited to, equivalent alternatives.

- accessible

authoring practice

- An accessible authoring practice is any authoring activity (e.g., inserting

an element, setting an attribute value), by either the author or the authoring

tool, that corrects an existing Web

content accessibility problem or does not cause a Web

content accessibility problem to be introduced.

- accessible

content support features

- All features of the tool that play a role in satisfying the success criteria

for checkpoints B.2.1, B.2.2,

B.2.3, B.2.5,

B.2.6 and B.2.7.

- alert

- An alert makes the author aware of events or

actions that require a response. The author response is not necessarily

required immediately. The events or actions that trigger an alert may have

serious consequences if ignored.

- audio

description

- Audio description (also called "Described Video") is an equivalent alternative that provides auditory information about

actions, body language, graphics, and scene changes in a video. Audio descriptions

are commonly used by people who are blind or have low vision, although they

may also be used as a low-bandwidth equivalent on the Web. An audio description

is either a pre-recorded human voice or a synthesized voice (recorded or

automatically generated in real time). The audio description must be synchronized

with the auditory track of a video presentation, usually with descriptions

occurring during natural pauses in the auditory track.

- author

- An author is the term used for the user of an authoring tool. This may

include content authors, designers, programmers, publishers, testers, etc.

- authored

"by hand"

- Authoring by hand is a situation in which the author

specifies Web content at the level to be

interpreted by the user agent (e.g., typing into a text editor, choosing

an element by name from a list).

- authoring

action

- An authoring action is any action that the author

takes using the authoring tool user

interface with the intention of adding or modifying Web

content (e.g., typing text, inserting an element, launching a wizard).

- authoring tool user interface

-

The user interface of the authoring tool is the display and control mechanism

that the author uses to communicate with and

operate the authoring tool software. Authoring tool interfaces may include (Note: tools may include both types of interfaces):

- Web-based functionality:

That part of an authoring tool user interface that is implemented using a content type and rendered on a user agent. Some authoring tools are fully Web-based (e.g., on-line content management system) others have components that are Web-based (e.g., a stand-alone markup editor with on-line help pages).

- non-Web-based functionality:

That part of an authoring tool user interface that runs directly on application execution environments such as

Windows, MacOS, Java Virtual Machine etc.

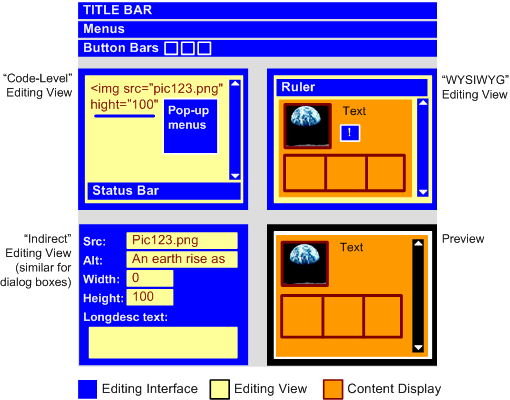

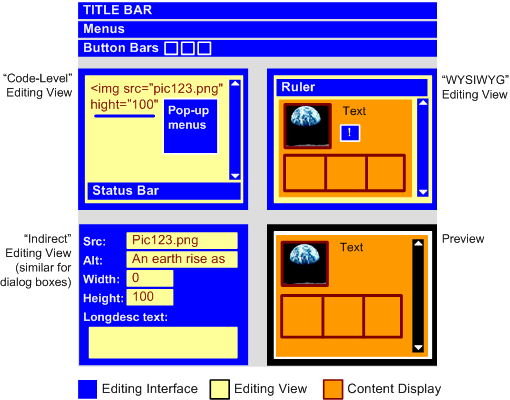

Most authoring tool user interfaces are composed of two parts:

- content

display: The rendering of the content to the author in the

editing view or preview. This might be as marked-up

content (i.e., in a code-level view), input field content (e.g., in an indirect

view, dialog boxes), or as rendered text, images, etc. (i.e., in a WYSIWYG

editing view).

- editing

interface: All of the parts of the user interface that are

not the content display (e.g., authoring tool menus, button bars, editing

view, pop-up menus, floating property bars, palettes, documentation

windows, cursor). These parts surround and in some cases are superimposed

on the content display. Preview views are not included in the editing interface because they are not editable.

Figure 2: An illustration of the parts of the authoring tool user interface as used in ATAG 2.0.

The graphic is a highly simplified representation of how the user interfaces of some GUI authoring tools are organized. The illustration includes four different views of the content: three editing views (a code-level editing view, a WYSIWYG editing view and an indirect editing view) and a preview view. Those parts of the user interface that are "editing interface" are colored dark blue, while the editing views are light blue and the content display is a mauve color. In the code-level editing view, the entire text entry area is considered the editing view and only the text within it is the content display. For the WYSIWYG editing view, since the background of the editing view is actually controlled by the content display (e.g., a rendered background color from the content - although see Checkpoint A.1.3) it too is considered to be content display. In the indirect editing view (and similarly for the dialog boxes used by many tools), the user is constrained to only providing some specific information (in this case some image attribute values and a long description). The text areas that collect this information are considered to be editing views while the text they contain is considered to be content display. The non-editable preview contains no editing view, just content display.

- authoring tool

- See "Definition of authoring tool".

- available

programmatically

- Capable of providing information to other software (including assistive

technologies) by following relevant accessibility platform architectures

(e.g., MSAA, Java Access) or, if the available accessibility platform architectures

are insufficient, following some other published interoperability mechanism

(custom-created by the developer, if necessary).

- captions

- Captions are equivalent

alternatives that consist of a text transcript of the auditory track

of a movie (or other video presentation) and that is synchronized with the

video and auditory tracks. Captions are generally rendered graphically.

They benefit people who are deaf or hard-of-hearing, and anyone who cannot

hear the audio (for example, someone in a noisy environment).

- checking, accessibility

- Accessibility checking (or "accessibility evaluation") is the

process by which Web content is evaluated

for Web content accessibility

problems. ATAG 2.0 identifies three types of checking, based on increasing

levels of automation: manual

checking in which the authoring tool only provides instructions

for authors to follow in order to identify problems; semi-automated

checking in which the authoring tool is able to identify potential

problems, but still requires human judgment by the author

to make a final decision on whether an actual problem exists; and automated

checking in which the authoring tool is able to check for problems

automatically, with no human intervention required. An authoring tool may

support any combination of checking types.

- completion

of authoring

- Completion of authoring is the point in time at which an authoring session

ends and the author has no opportunity to make further changes. This may

be when an author chooses to "save and exit", or "publish",

or it may occur automatically at the end of a wizard, etc.

- content type

- A content type is a data format, programming or markup language that is

intended to be retrieved and rendered by a user

agent (e.g., HTML, CSS, SVG, PNG, PDF, Flash, JavaScript or combinations).

The usage of the term is a subset of WCAG 2.0's [WCAG20]

current usage of the term "Technology".

- conversion

- A conversion is a process that takes as input, content in one content

type and produces as output, content in another content

type (e.g., "Save as HTML" functions).

- document

- A document is a structure of elements along

with any associated content; the elements used are defined by a markup language.

- documentation

- Documentation refers to any information that supports the use of an authoring

tool. This information may be found electronically or otherwise and includes

help, manuals, installation instructions, sample workflows,

and tutorials, etc.

- editing

view

- An editing view is a view provided by the authoring tool that

allows editing by the author (e.g., code-level editing

view, WYSIWYG editing view).

- element

- Element is used in the same sense as in HTML [HTML4] and XML, an element refers to a pair of tags and their

content, or an "empty" tag - one that requires no closing tag

or content.

- end user

- An end user is a person who interacts with Web

content once it has been authored. In some cases, the author

and end user is the same person.

- equivalent

alternative

- An equivalent alternative is content that is an acceptable substitute

for other content that a person may not be able to access. An equivalent

alternative fulfills essentially the same function or purpose as the original

content upon presentation. Equivalent alternatives include text alternatives

and synchronized alternatives. Text

alternatives present a text version of the information conveyed

in non-text objects such as graphics and audio clips. The text alternative

is considered accessible because it can be rendered in many different ways

(e.g., as synthesized speech for individuals who have visual or learning

disabilities, as Braille for individuals who are blind, as graphical text

for individuals who are deaf or do not have a disability). Accessible

multimedia alternatives present the same information as is conveyed

in the multimedia via accessible text, navigation,

forms, etc. Synchronized

alternatives present essential audio information visually (i.e.,

captions) and essential

video information in an auditory manner (i.e., audio descriptions).

- freeform

drawing

- Drawing actions that use the mouse or stylus in a continuous fashion (e.g.,

a paintbrush feature). This does not cover moving or resizing object-based

graphics (including moving or resizing an object that is a previously authored

freeform graphic).

- general

flash or red flash

- General flash threshold (Based on Wisconsin Computer Equivalence Algorithm for Flash Pattern

Analysis (FPA)): A sequence of flashes or rapidly changing

image sequences where all three of the following occur:

- the combined area of flashes occurring concurrently (but not necessarily

contiguously) occupies more than one quarter of any 341 x 256 pixel

rectangle anywhere on the displayed screen area when the content is

viewed at 1024 x 768 pixels;

- there are more than three flashes within any one-second period; and

- the flashing is below 50 Hz.

- (Note: For the general flash threshold, a flash is defined

as a pair of opposing changes in brightness of 10% or more of full scale

white brightness, where brightness is calculated as 0.2126 * ((R / FS) ^

2.2) + 0.7152 * ((G / FS) ^ 2.2) + 0.0722 * ((B / FS) ^ 2.2). R, G, and

B are the red, green, and blue RGB values of the color; FS is the maximum

possible full scale RGB value for R, G, and B (255 for eight bit color channels);

and the "^" character is the exponentiation operator. An "opposing

change" is an increase followed by a decrease, or a decrease followed

by an increase. This applies only when the brightness of the darker image

is below .80 of full scale white brightness.

- Red flash threshold (Based on Wisconsin Computer Equivalence Algorithm for Flash Pattern

Analysis (FPA)): A transition to or from a saturated red where

both of the following occur:

- The combined area of flashes occurring concurrently occupies more

than one quarter of any 341 x 256 pixel rectangle anywhere on the displayed

screen area when the content is viewed at 1024 x 768 pixels.

- There are more than three flashes within any one-second period.

- The flashing is below 50 Hz.

- inform

- To inform is to make the author aware of an

event or situation using methods such as alert, prompt, sound, flash. These methods may

be unintrusive (i.e., presented without stopping the author's current activity)

or intrusive (i.e., interrupting the author's current activity).

- informative

- Informative ("non-normative") parts of this document are never

required for conformance.

- keyboard interface

- Interface used by software to obtain keystroke input.

Note 1: Allows users to provide keystroke input to programs even if the native technology does not contain a keyboard (e.g., a touch screen PDA has a keyboard interface built into its operating system as well as a connector for external keyboards. Applications on the PDA can use the interface to obtain keyboard input either from an external keyboard or from other applications that provide simulated keyboard output, such as handwriting interpreters or speech to text applications with "keyboard emulation" functionality).

Note 2: Operation of the application (or parts of the application) through a keyboard operated mouse emulator, such as MouseKeys, does not qualify as operation through a keyboard interface because operation of the program is through its pointing device interface - not through its keyboard interface.

- markup

- Markup is a set of tags from a markup language

that specify the characteristics of a document.

Markup can be presentational (i.e., markup that encodes

information about the visual layout of the content), structural

(i.e., markup that encodes information about the structural role of elements

of the content) or semantic (i.e., markup that encodes

information about the intended meaning of the content).

- markup language

- A markup language is a syntax and/or set of rules to manage markup

(e.g., HTML [HTML4], SVG [SVG], or MathML [MATHML]).

- multimedia

- Audio or video synchronized with another type of media and/or with time-based

interactive components.

- non-text

objects

- Content objects that are not represented by text character(s) when rendered

in a user agent (e.g., images, audio, video).

- normative

- Normative parts of this document are always required for conformance.

- platform

- A platform is the software environment within which the authoring tool operates. For functionality that is not Web-based, this will be an operating system (e.g., Windows, MacOS, Linux), virtual machine (e.g., JVM) or a higher level GUI toolkit (e.g., Eclipse). For Web-based functionality, the term applies more generically

to user agents in general, although for purposes of evaluating

conformance to ATAG 2.0, a specific user agent(s) will be listed in the conformance profile.

- presentation

- Presentation is the rendering of the content and structure in a form that

can be perceived by the user.

- preview

- A preview is a non-editable view of the content that is intended to show how it will

appear and behave in a user agent.

- prominence

- The prominence of a control in the authoring

tool user interface is a heuristic measure of the degree to which authors

are likely to notice a control when operating the authoring tool. In this

document, prominence refers to visual as well as keyboard-driven navigation.

Some of the factors that contribute to the prominence of a control include:

control size (large controls or controls surrounded by

extra white space may appear to be conferred higher importance), control

order (items that occur early in the "localized" reading

order (e.g., left to right and top to bottom; right to left and top to bottom)

are conferred higher importance), control grouping (grouping

controls together can change the reading order and the related judgments

of importance), advanced options (when the properties are

explicitly or implicitly grouped into sets of basic and advanced properties,

the basic properties may gain apparent importance), and highlighting

(controls may be distinguished from others using icons, color, styling).

- prompt

- In this document "prompt" refers to any authoring tool initiated request for a decision or piece of information. Well designed prompting will urge, suggest, and encourage the author.

- repairing,

accessibility

- Accessibility repairing is the process by which Web

content accessibility problems that have been identified within Web

content are resolved. ATAG 2.0 identifies three types of repairing,

based on increasing levels of automation: Manual

repairing in which the authoring tool only provides instructions

for authors to follow in order to make the necessary correction; Semi-Automated

repairing, in which the authoring tool can provide some automated assistance

to the author in performing corrections, but the author's input is still

required before the repair can be completed; and Automated

repairing, in which the authoring tool is able to make repairs automatically,

with no author input or confirmation from the

author. An authoring tool may support any combination of repairing types.

- selectable

items

- Any items that an author may select from within the menus, toolbars, palettes,

etc. (e.g., "open", "save", "emphasis", "check

spelling")

- structured

element set

- Content organized into lists, maps, hierarchies (e.g., tree views), graphs,

etc.

- transcript

- A transcript is a non-synchronized text

alternative for the sounds, narration, and dialogue in an audio clip

or the auditory track of a multimedia presentation. For a video, the transcript

can also include the description of actions, body language, graphics, and

scene changes of the visual track.

- transformation

- A transformation is a process that takes as input, an object in one content

type and produces as output, a different object in the same content

type (e.g., a function that transforms tables into lists).

- user

Agent

- A user agent is software that retrieves and renders Web content. This

may include Web browsers, media players, plug-ins, and other programs including

assistive technologies, that help in retrieving and rendering Web content.

- view

- A view is a rendering of Web content by

an authoring tool. Authoring tool views are usually either editing

views or previews.

- Web content (or shortened to "content")

- Web content is any material in a content type. If the content type is a markup language, then "content" covers the information both within the tags (i.e., the markup) and between them. In this document, "content" is primarily used in the context of the material that is authored and outputted by authoring tools.

- Wisconsin Computer

Equivalence Algorithm for Flash Pattern Analysis (FPA)

- a method developed at the University of Wisconsin, working in conjunction

with Dr. Graham Harding and Cambridge Research Associates, for applying

the United Kingdom's "Ofcom Guidance Note on Flashing Images and Regular

Patterns in Television (Re-issued as Ofcom Notes 25 July 2005)" to

content displayed on a computer screen, such as Web pages and other computer

content.

Note: The Ofcom Guidance Document [OFCOM]

is based on the assumption that the television screen occupies the central

ten degrees of vision. This is not accurate for a screen which is located

in front of a person. The Wisconsin algorithm basically carries out the

same analysis as the Ofcom Guidelines except that is does it on every possible

ten degree window for a prototypical computer display.

- workflow

- A workflow is a customary sequence of steps or tasks that are followed

to produce a deliverable.

5. References

For the latest version of any W3C

specification please consult the list of W3C

Technical Reports at http://www.w3.org/TR/. Some documents listed below

may have been superseded since the publication of this document.

Note: In this document, bracketed labels such as "[HTML4]"

link to the corresponding entries in this section. These labels are also

identified as references through markup. Normative references are highlighted

and identified through markup.

There are two recommended ways to refer to the "Authoring Tool Accessibility

Guidelines 2.0" (and to W3C documents in general):

- References to a specific version of "Authoring

Tool Accessibility Guidelines 2.0." For example, use the "this

version" URI to refer

to the current document: http://www.w3.org/TR/2006/WD-ATAG20-20061207/.

- References to the latest version of "Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines

2.0." Use the "latest version" URI to refer to the most recently published

document in the series: http://www.w3.org/TR/ATAG20/.

In almost all cases, references (either by name or by link) should be to a

specific version of the document. W3C will make every effort to make this

document indefinitely available at its original address in its original form.

The top of this document includes the relevant catalog metadata for specific

references (including title, publication date, "this version"

URI, editors' names, and copyright information).

An XHTML 1.0 paragraph including a

reference to this specific document might be written:

<p>

<cite><a href="http://www.w3.org/TR/2006/REC-ATAG20-????????/">

"Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines 2.0,"</a></cite>

J. Treviranus, J. Richards, M. May, eds.,

W3C Recommendation, ?? ???? ????.

The <a href="http://www.w3.org/TR/ATAG20/">latest

version</a> of this document is available at

http://www.w3.org/TR/ATAG20/.</p>

For very general references to this document (where stability of content and

anchors is not required), it may be appropriate to refer to the latest version

of this document.

Other sections of this document explain how to build a conformance

claim.

A document appears in this section if at least one reference to the document

appears in a checkpoint success criteria.

- [WCAG10]

- "Web Content

Accessibility Guidelines 1.0", W. Chisholm, G. Vanderheiden, and I. Jacobs,

eds., 5 May 1999. This WCAG 1.0 Recommendation is

http://www.w3.org/TR/1999/WAI-WEBCONTENT-19990505/.

- [WCAG20]

- "Web Content Accessibility

Guidelines 2.0 (Working Draft)", W. Chisholm, G. Vanderheiden,

and J. White, editors. The latest version of the Web Content Accessibility

Guidelines 2.0 is available at http://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG20/. Note:

This document is still a working draft.

- [ATAG10]

- "Authoring Tool Accessibility

Guidelines 1.0", J. Treviranus, C. McCathieNevile, I. Jacobs, and J.

Richards, eds., 3 February 2000. This W3C Recommendation is available at http://www.w3.org/TR/2000/REC-ATAG10-20000203/.

-

-

- [ATAG20-TECHS]

- "Techniques for Authoring

Tool Accessibility 2.0", J. Treviranus, J. Richards, C. McCathieNevile,

and M. May, eds., 22 November 2004. The latest draft of this W3C note is available at http://www.w3.org/TR/ATAG20-TECHS.

- [COMPONENTS]

- "Essential Components of Web Accessibility", S. L. Henry, ed. This document is available at http://www.w3.org/WAI/intro/components.

- [CSS2-ACCESS]

- "Accessibility

Features of CSS," I. Jacobs and J. Brewer, eds., 4 August 1999. This W3C

Note is available at http://www.w3.org/1999/08/NOTE-CSS-access-19990804. The latest

version of Accessibility Features of CSS is available at http://www.w3.org/TR/CSS-access.

- [HTML4]

- "HTML 4.01 Recommendation",

D. Raggett, A. Le Hors, and I. Jacobs, eds., 24 December 1999. This

HTML 4.01 Recommendation is http://www.w3.org/TR/1999/REC-html401-19991224.

The latest version of HTML 4 is available at

http://www.w3.org/TR/html4.

- [MATHML]

- "Mathematical Markup Language",

P. Ion and R. Miner, eds., 7 April 1998, revised 7 July 1999. This MathML

1.0 Recommendation is http://www.w3.org/1999/07/REC-MathML-19990707. The

latest version of MathML 1.0 is available

at http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-MathML.

- [OFCOM]

- Guidance Notes, Section 2: Harm and offence Annex 1, "Ofcom Guidance Note on Flashing Images and Regular Patterns in Television (Re-issued as Ofcom Notes 25 July 2005)" available at http://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv/ifi/guidance/bguidance/guidance2.pdf)

- [PWD-USE-WEB]

- "How

People With Disabilities Use the Web", J. Brewer, ed., 4 January

2001. This document is

available at http://www.w3.org/WAI/EO/Drafts/PWD-Use-Web/.

- [SMIL-ACCESS]

- "Accessibility

Features of SMIL," M.-R. Koivunen and I. Jacobs, eds., 21 September 1999. This W3C Note is available at available at http://www.w3.org/TR/SMIL-access.

- [SVG]

- "Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) 1.0

Specification (Working Draft)", J. Ferraiolo, ed. The latest version

of the SVG specification is available at http://www.w3.org/TR/SVG.

- [SVG-ACCESS]

- "Accessibility of Scalable Vector

Graphics," C. McCathieNevile, M.-R. Koivunen, eds., 7 August 2000. This W3C Note is available at http://www.w3.org/TR/SVG-access.

- [WCAG10-TECHS]

- "Techniques for Web Content

Accessibility Guidelines 1.0," W. Chisholm, G. Vanderheiden, and I. Jacobs,

eds., 6 November 2000. This W3C Note is available at http://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG10-TECHS/.

- [WCAG20-TECHS-GENERAL]

- "General Techniques for WCAG 2.0," J. Slatin, T. Croucher,

eds. Note: This document is still a working draft.

- [WCAG20-TECHS-CSS]

- "CSS Techniques for WCAG 2.0," W. Chisholm, B. Gibson,

eds. Note: This document is still a working draft.

- [WCAG20-TECHS-HTML]

- "HTML Techniques for WCAG 2.0," M. Cooper,

ed. Note: This document is still a working draft.

- [WCAG20-TECHS-SCRIPTING]

- "Client-side Scripting Techniques for WCAG 2.0," M. May, B. Gibson,

eds. Note: This document is still a working draft.

- [WCAG20-UNDERSTANDING]

- "Understanding WCAG 2.0," B. Caldwell, W. Chisholm, J. Slatin, G. Vanderheiden, eds. Note: This document is still a working draft.

- [XAG]

- "XML Accessibility Guidelines",

D. Dardailler, S. B. Palmer, C. McCathieNevile, eds. 3 October 2002.

This is a Working Group Draft.

6. Acknowledgments

The active participants of the Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines Working

Group who authored this document were: Tim Boland (National Institute for

Standards and Technology), Barry A. Feigenbaum (IBM), Matt May, Greg Pisocky (Adobe), Jan Richards (Adaptive

Technology Resource Centre, University of Toronto), Roberto Scano (IWA/HWG),

and Jutta Treviranus (Chair of the working group, Adaptive Technology Resource

Centre, University of Toronto)

Many thanks to the following people who have contributed to the AUWG through

review and comment: Kynn Bartlett, Giorgio Brajnik, Judy Brewer, Wendy Chisholm,

Daniel Dardailler, Geoff Deering, Katie Haritos-Shea, Kip Harris, Phill

Jenkins, Len Kasday, Marjolein Katsma, William Loughborough, Charles McCathieNevile,

Matthias Müller-Prove, Liddy Nevile, Graham Oliver, Wendy Porch, Bob

Regan, Chris Ridpath, Gregory Rosmaita, Heather Swayne, Gregg Vanderheiden,

Carlos Velasco, and Jason White.

This document would not have been possible without the work of those who contributed to ATAG 1.0.

This publication has been funded in part with Federal funds from the U.S. Department of Education under contract number ED05CO0039. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Education, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.