Abstract

CSS is a simple, declarative language for creating style sheets that

specify the rendering of HTML and other structured documents. This

specification is part of level 3 of CSS and contains

features to describe layouts at a high level, meant for tasks such as the

positioning and alignment of “widgets” in a graphical user interface

or the layout grid for a page or a window, in particular when the desired

visual order is different from the order of the elements in the source

document. Other CSS3 modules contain properties to specify fonts, colors,

text alignment, list numbering, tables, etc.

The features in this module are described together for easier reading,

but are usually not implemented as a group. CSS3 modules often depend on

other modules or contain features for several media types. Implementers

should look at the various “profiles” of CSS, which list consistent

sets of features for each type of media.

The contents of this document are still highly experimental.

Status of this document

This section describes the status of this document at the time of

its publication. Other documents may supersede this document. A list of

current W3C publications and the latest revision of this technical report

can be found in the W3C technical reports

index at http://www.w3.org/TR/.

Publication as a Working Draft does not imply endorsement by the W3C

Membership. This is a draft document and may be updated, replaced or

obsoleted by other documents at any time. It is inappropriate to cite this

document as other than work in progress.

The (archived) public

mailing list www-style@w3.org (see

instructions) is preferred

for discussion of this specification. When sending e-mail, please put the

text “css3-layout” in the subject, preferably like this:

“[css3-layout] …summary of

comment…”

This document was produced by the CSS

Working Group (part of the Style Activity).

This document was produced under the 24 January 2002 CPP as

amended by the W3C Patent Policy

Transition Procedure. The Working Group maintains a public list of patent

disclosures relevant to this document; that page also includes

instructions for disclosing a patent. An individual who has actual

knowledge of a patent which the individual believes contains Essential

Claim(s) with respect to this specification should disclose the

information in accordance with section 6

of the W3C Patent Policy.

This is the first version of the draft.

Table of contents

1. Dependencies on other

modules

This CSS3 module depends on the following other CSS3 modules:

It has non-normative (informative) references to the following other

CSS3 modules:

2. Introduction

(This section is not normative.)

The styling of a Web page, a form or a graphical user

interface can roughly be divided in two parts: (1) defining the

overall“grid” of the page or window and (2) specifying the fonts,

indents, colors, etc., of the text and other objects. The two are not

completely separate, of course, since indenting or coloring a text

influences the perceived grid as well. Nevertheless, when one separates

the parts of a style that should change when the window gets bigger, from

the parts that stay the same, one often finds that the grid changes (room

for a sidebar, extra navigation bar, big margins, larger images…), while

fonts, colors, indents, numbering styles, and many other things don't have

to change, until the size of the window becomes extreme.

The properties in this specification work by associating a layout

policy with an element. Rather than making an element lay out its

descendants in their normal order as inline text or as blocks of text with

margins (the policies available in CSS level 1), these policies cause

an element to define an invisible grid, in which descendant element will

be placed. One policy also allows elements to be stacked similar to tabbed

cards, of which only one is visible at any time.

Since layouts on the Web have to deal with different window and paper

sizes, the rows and columns of the grid can be made fixed or flexible in

size.

The typical use cases for these properties include:

- Complex Web pages, with multiple navigation bars in fixed positions,

areas for advertisements, etc.

- Complex forms, where the alignment of labels and form fields may be

easier with the properties of this module than with the properties for

tables and margins.

- GUIs, where buttons, toolbars, labels, icons, etc., are aligned in

complex ways and have to stay aligned (and not wrap, for example) when

the window is resized.

- Tabbed dialog boxes, with only one “card” visible at any one time.

3. Template-based

positioning

Template-based positioning is an alternative to absolute positioning,

which, like absolute positioning, is especially useful for aligning

elements that don't have simple relationships in the source (parent-child,

ancestor-descendant, immediate sibling). But in contrast to absolute

positioning, the elements are not positioned with the help of horizontal

and vertical coordinates, but by mapping them into slots in a table-like

template. The relative size and alignment of elements is thus governed

implicitly by the rows and columns of the template. It doesn't allow

elements to overlap, but it provides layouts that adapt better to

different widths.

The mapping is done with the 'position' property, which specifies in this

case into which slot of the template the element goes. The template itself

is specified as a string value on the 'display-model' (or 'display') property of some

ancestor of the elements to remap.

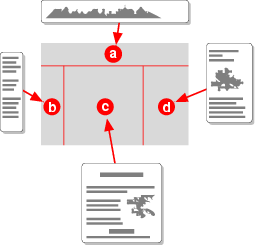

In this example, the four children of an element are assigned to four

slots (called a, b, c and d) in a 2×2 template.

<style type="text/css">

dl { display: "ab"

"cd" }

#sym1 { position: a }

#lab1 { position: b }

#sym2 { position: c }

#lab2 { position: d }

</style>

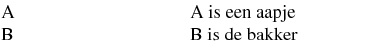

<dl>

<dt id=sym1>A

<dd id=lab1>A is een aapje

<dt id=sym2>B

<dd id=lab2>B is de bakker

</dl>

Rather than letters, we could use x's and numbers:

<style type="text/css">

dl { display: "x:x"

":::"

"x:x") }

#sym1 { position: 1 1 }

...

Templates can also help with device-independence. This example uses

Media Queries [MEDIAQ] to change the overall

layout of a page from 3-column layout for a wide screen to a 1-column

layout for a narrow screen. It assumes the page has been marked-up with

logical sections with IDs.

@media all

{

body { display: "aaa"

"bcd" }

#head { position: a }

#nav { position: b }

#adv { posiiton: c }

#body { position: d }

}

@media all and (max-width: 500px)

{

body { display: "a"

"b"

"c" }

#head { position: a }

#nav { position: b }

#adv { display: none }

#body { position: c }

}

Elements can be positioned this way, but not made to overlap, unless

with negative margins. Here is how the

“zunflower” design of the Zen Garden could be done:

#container { display: "abc" }

#intro { position: a; margin-right: -2em; box-shadow: 0.5em 0.5em 0.5em }

#supportingText { position: b; box-shadow: 0.5em 0.5em 0.5em }

#linkList { position: c }

3.1. Declaring templates: the

'display-model'

property

An element with this 'display-model' is similar to a table

element. Its content is laid out in rows and columns. The two main

differences are that the number of rows and columns doesn't depend on the

content, but is fixed by the value of the property; and that the order of

the descendants in the source document may be different from the order in

which they appear in the rendered template.

Each string consist of one or more letters (see <letter> below), at signs (“@”) and

periods (“.”). Each string represents one row in the template, each

character one column in that row.

The symbols in the template have the following meaning

- a letter

- slot for content.

- @

- (at sign) default slot for content.

- .

- (period) whitespace.

Multiple identical letters in adjacent rows or columns form a single

slot that spans those rows and columns. Ditto for

multiple “@”s. Uppercase and lowercase are considered to be the same

letter.

Non-rectangular slots are illegal. A template without any letter or

“@” is illegal. A template with more than one “@” slot is illegal.

These errors cause the declaration to be ignored.

Non-rectangular regions can be tricky to implement (constraint-solving

in case there is any part with intrinsic size instead of fixed size) but

could be interesting. Here is a nice layout for text and images that you

can't get with floating:

body { display: "a@@"

"@@@"

"@@b"

"@@@"

"c@@"

"@@@"

"@@d" }

img { width: 100%; fit: meet; fit-position: 50% 50% }

img#a { position: a }

img#b { position: b }

img#c { position: c }

img#d { position: d }

Without a fixed height for the body element, the UA will have to try

various heights until the smallest one is found that causes the content

of the body to fit without vertical overflow…

Rows with fewer columns than other rows are implicitly padded with

periods (“.”) (that will thus not contain any elements).

Each slot (letter or “@”) acts as a block, as if it were an element

with 'display-model' set to 'block-inside'.

Each <row-height> sets the

height of the preceding row. The default is '*'.

The values can be as follows:

- <length>

- An explicit height for that row. Negative values make the template

illegal.

- intrinsic

- The row's height is determined by its contents. See the algorithm below.

- *

- (asterisk) All rows with an asterisk will be of equal height. See the

algorithm below.

Each <col-width> sets the

width of a column. If there are more <col-width>s then columns, the last

ones are ignored. If there are fewer, the missing ones are assumed to be

'*'. Each <col-width> can be one of the

following:

- <length>

- An explicit width for that column. Negative values make the template

illegal.

- *

- (asterisk.) All columns with a

'*' have the

same width. See the algorithm below.

- intrinsic

- The column's width is determined by its contents. See the algorithm below.

Note that it is legal to specify no widths at all. In that

case, all columns have the same width.

The orientation of the template is independent of the writing mode

('direction' and

'writing-mode'

properties): the first string is the topmost row and the first symbol in

each string is the leftmost column.

<style type="text/css">

div { display: “.aa..bb.” }

p.left { position: a }

p.right { position: b }

</style>

<div>

<p class=left>Left column

<p class=right>Right column

</div>

An element with a template value for its 'display-model' property is called a template element. An element's template ancestor is defined (recursively) as follows:

- if the element has

'position: fixed', 'position: absolute', a value of 'float' that is not 'none' or the element is the root element, than it has

no template ancestor. [Check if this is a “flow

root”.]

- else, if the element's parent has a template as its 'display-model', then

that parent is the element's template ancestor.

- else, the element's template ancestor is the same as its parent's

template ancestor.

3.2. Computing the width of the

slots

The layout algorithm distinguishes the case of an

element of a-priori known width and a shrink-wrapped element. In the

former case, the target width of the template is the

width of the element itself; in the latter case, the target width is the

width of the initial containing block [need ref.] (often the viewport).

The width may be unknown, if, e.g., 'width' is 'auto' and the

element is floating, absolutely positioned, inline-block or inside a block

with vertical writing mode.

If the sum of the minimum intrinsic widths (defined below) of the

columns is larger than the target width,

each column is set to its minimum intrinsic

width and the element will overflow (see 'overflow'). If the sum is less than the

target width, the columns are widened until

the total width is equal to the target

width, as follows: all columns get the same width, except that no

column or span of columns may be wider than its maximum intrinsic width.

The intrinsic widths are defined as follows:

-

A column with a <col-width> of a given

<length> has minimum and maximum intrinsic widths both

equal to that <length>.

-

A column with a <col-width> of '*' has an infinite maximum intrinsic width. Its

minimum intrinsic width is 0.

-

A column with a <col-width> of 'intrinsic' has a minimum intrinsic width equal to the

maximum over the minimum intrinsic widths of all the slots in that

column:

- The minimum intrinsic width of a “.” is 0.

- The minimum intrinsic width of a letter or “@” slot is 0 if that

slot spans two or more columns; it is the minimum intrinsic width of

the contents of the slot if it spans only one column.

The column has a maximum intrinsic width equal to the largest of the

maximum intrinsic widths of all the slots in that column:

- The maximum intrinsic width of a “.” is 0.

- The maximum intrinsic width of a letter or “@” is the maximum

intrinsic width of the contents of that slot.

-

The minimum intrinsic width of each span of one or more columns is the

maximum over all the minimum intrinsic widths of all slots and

whitespace that span exactly those columns.

Analogously, the maximum intrinsic width of each span of one or more

columns is the maximum over all the maximum intrinsic widths of the

slots and whitespace that span exactly those columns.

Note that the widths of the columns can be completely

determined before laying out any of the contents as long as there are no

columns with a <col-width>

of 'intrinsic'.

If the element has an a-priori width and the columns cannot be widened

enough to fill that target width, the template is left or right aligned in

the element's content area, depending on whether 'direction' is 'ltr'

or 'rtl', respectively.

3.3. Computing the height of the

slots

The height of the template is the smallest possible under the following

constraints:

- Rows with a height set to <length> have that height.

- No row has a negative height.

- All rows with a height set to

'*' are the same

height.

- Every sequence of one or more rows of which at least one has a height

set to

'intrinsic' is at least as high as every

letter or “@” slot that spans exactly that sequence of rows.

- If the computed value of the element's 'height' is

'auto', then

every sequence of one or more rows of which at least one has a height set

to '*' is at least as high as every letter or

“@” slot that spans exactly that sequence of rows.

- The whole template is at least as high as the computed value of the

element's 'height',

unless that value is

'auto'.

This leads to a contradiction in the case that all rows have

a fixed height and their sum is less than the fixed height of the template

element: 'display: "xxx" (2em); height: 3em}'

The height of a slot is measured from the top margin edge of the topmost

element to the bottom margin edge of the bottommost element, exactly as if

the slot was the root of a block formatting context and the elements

positioned in it its children. [Make a link to block

formatting context in CSS 2.1 or in the Box model.]

This example divides the window in three rows and three columns,

separated by 1em of white space. The middle row and the middle column are

flexible, the others are fixed at a specific size. The first column is

5em wide, the last one 10em.

<style type="text/css">

body {

height: 100%;

display: "a.b.c" (2em)

"....." (1em)

"d.e.f"

"....." (1em)

"g.h.i" (2em)

5em 1em * 1em 10em}

#logo {position: a}

#motto {position: b}

#date {position: c}

#main {position: e}

#adv {position: f}

#copy {position: g}

#about {position: h}

</style>

<p id=logo><img src=...

<p id=motto>Making Web pages since 1862

<p id=date>August 2, 2004

...

3.4. Flowing content into the

template: the 'position' property

| Name:

| position

|

| New value:

| <letter> | same

|

| Percentages:

| N/A

|

| Computed value:

| '<letter>' or 'static'; see text

|

This value of the 'position' property specifies into which row

and column of a template the element is placed. The <letter> must be a single letter, with category

Lu, Ll or Lt in Unicode [UNICODE]), or a “@” symbol.

- <letter>

- The element is taken out of the flow of its parent and put into the

specified slot in its template

ancestor. If there is no slot of that name, the computed value

is

'static'.

- same

- A value of

'same' instead of a letter computes

to the same letter as the most recent element with a letter as position

that has the same template

ancestor. If there is no such element, the value computes to 'static'.

The containing block of an element with one

of these values for 'position' is the slot in the template into

which it is flowed.

Multiple elements may be put into the same slot. They will be layed-out

according to their 'display-role' property in

the order they occur in the source document.

The content of a template element is

put in the slot marked with “@”s. If there is no such slot, the

content is put in the the first (leftmost) slot on the first row that

doesn't consist of only “.”.

The FIG element, that was once proposed for HTML, has an attribute that

points to an image, a CAPTION child and some fallback text. The template

below uses “@” to indicate where the image (or the fallback) goes, in

relation to the caption.

/* <FIG SRC=...><CAPTION>...</> Fallback</> */

FIG {

/* See Generated Content Module */

content: attr(SRC, url), normal;

/* Caption may be wider than image */

display: ".@."

"xxx"

* intrinsic * }

CAPTION { position: x }

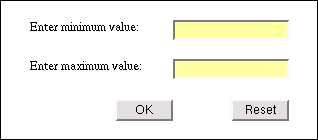

In this example, a form is layed out on a grid, with two labels and two

input boxes and a submit and a reset button:

form {

border: thin solid;

display: "aaaa.bbbb"

"........."

"cccc.dddd"

"........."

"...ee..ff" }

label[for=minv] { position: a }

input#minv { position: b; display: block }

label[for=maxv] { position: c }

input#maxv { position: d; display: block }

input[type=submit] { position: e; display: block }

input[type=reset] { position: f; display: block }

Here is the fragment of HTML that the style is applied to:

<form action="./">

<label for=minv>Enter minimum value:</label>

<input id=minv name=minv>

<label for=maxv>Enter maximum value:</label>

<input id=maxv name=maxv>

<input type=submit value="OK">

<input type=reset value="Reset">

</form>

The addition of 'display: block' causes the form

controls to use the width computation of blocks, in other words: they

will be as wide as their containing block, which in this case means that

they will be as wide as the slot they are assigned to. Without it, they

would be inline elements and just be left-aligned in their slots.

This example shows that templates can be nested. The body has two

columns. The #content element that goes into the second column has itself

another template, into which the various “modules” are

placed.

For clarity, the inner template uses different letters for the slots

than the outer template. This is not required.

<style type="text/css">

body {

display: "a.b"

200px *;

}

#nav {

position: a;

}

#content {

position: b;

display: "c.d.e"

"....."(1em)

"..f..";

}

.module.news {

position: c;

}

.module.sports {

position: d;

}

.module.personal {

position: e;

}

#foot {

position: f;

}

</style>

<body>

<ul id="nav">

<li>navigation</li>

</ul>

<div id="content">

<div class="module news">

<h3>Weather</h3>

<p>There will be weather</p>

</div>

<div class="module sports">

<h3>Football</h3>

<p>People like football.</p>

</div>

<div class="module sports">

<h3>Chess</h3>

<p>There was a brawl at the chess tournament</p>

</div>

<div class="module personal">

<h3>Your Horoscope</h3>

<p>You're going to die (eventually).</p>

</div>

<p id="foot">Copyright some folks</p>

</div>

</body>

3.5. Vertical alignment

The 'vertical-align' property can be used to

align elements vertically in a slot. It only applies to an element that is

block-level, that is the first (or the only) element in the slot and that

doesn't float. In that case, the values have the following meaning:

- bottom

- The element(s) in this slot is (are) aligned to the bottom of the

slot: the top padding of this element is stretched, so that the height

from the top margin edge of this element to the bottom margin edge of the

last element in this slot is equal to the height of the row. [Borrow from

10.6.7 in CSS 2.1 for a more precise formulation, including floats]

- middle

- The element(s) in this slot is (are) vertically centered in the slot:

the top padding of this element and the bottom padding of the last

element are increased by the same amount, so that the height from the top

margin edge of this element to the bottom margin edge of the last element

in this slot is equal to the height of the row.

- baseline

- The top padding of this element is increased just enough that the

baseline of the element's first line box is level with the baseline of

the first line box of of all other slots in this row that have a first

element with

'vertical-align: baseline'. The

bottom padding of the last element is increased so that its bottom margin

edge is flush with the bottom of the row.

For all other values and other cases, the elements are top aligned,

i.e., the bottom padding of the last element in the slot is increased, so

that the height from the top margin edge of the element to the bottom

margin edge of the last element in this slot is equal to the height of the

row.

Other options: (1) define something like a 'block-align' property to replace 'vertical-align'; (2) ditto, but call it 'display-align' as in XSL; (3) add flexible padding

and/or margin ('padding-top: auto' or 'margin-top:

auto'); (4) indicate the alignment with different letters in the

template, use a, m and z instead of x. (The latter will maybe be too many

letters to remember…)

Do we need templates that automatically grow to the required

number of rows and columns? Could they also grow to the left and up? Have

the template automatically orient according to the 'direction' or 'writing-mode' property of the template

element?

3.6. Overflow

If content overflows a slot, it is displayed. The effect is as if the

slot had an 'overflow'

property of 'visible'. The section “Stacking order” (below) specifies

which element is in front if two elements overlap.

3.7. Templates in paged media

In paged media (see [definition is where?]), a template element may be broken over several

pages. Page breaks may occur between rows or inside rows, in both cases

depending on the page break properties of the contents of the slots (see

[CSS3PAGE]).

If content in different columns has conflicting page break values for

the same break point, a value of 'right' overrides

'left', which overrides 'always', which in turn overrides 'avoid'.

For example, if the first element in a slot has 'page-break-before' set to 'avoid', the UA should try to avoid breaking the page

before this row, unless the first element in another slot in the same row

has a value of 'always'.

Note that a template element may be made as high as the page

box by setting its 'height' to '100vh' (see

[CSS3VAL]).

[This doesn't seem to be defined explicitly in either

Values & Units or in Paged Media…] Templates cannot be used

to set the areas of a page. Use '@top-left', '@top-center' for that.

The following style might be used for a slide show presentation, with a

title and two columns on each slide:

@media projection

{

div.slide {

display: "aaa" (2em) "b.c";

height: 100vh;

page-break-before: always }

h1 { position: a }

div.left { position: b }

div.right { position: c }

}

for a source mark-up similar to this:

<div class=slide>

<h1>Title of this slide

<div class=left>

<p>Content for left pane

<div>

<div class=right>

<p>Content for right pane

</div>

</div>

The approach above requires that the whole subtree of a template

element is processed before the resulting template is broken into pages.

But if the device's memory is limited to not much more than one

page-worth of data, that may not work.

Maybe another approach is possible, in which pages are split earlier.

For example, a new page may start before an element that would be

positioned in a template, if that template itself is in the main flow.

In that case, the question is how to lay out the rest of the elements:

create another identical template and put them in that? or lay out the

elements as if they had no template ancestor?

Creating another template is attractive. It allows the slide show

example above to be simplified and no longer require the div.slide:

@media projection

{

body {

display: "aaa" (2em) "b.c";

height: 100vh }

h1 {

position: a;

page-break-before: always }

div.left { position: b }

div.right { position: c }

}

for a source mark-up similar to this:

<h1>Title of this slide

<div class=left>

<p>Content for left pane

<div>

<div class=right>

<p>Content for right pane

</div>

3.8. Stacking order

An element with a computed value of a letter for its 'position' is a

positioned element (see [CSS3POS]) and thus the 'z-index' property applies to

it. The general rules for stacking contexts

[ref in CSS3?] apply.

Note that an element can only have such a computed value if

it has an ancestor that is a template

element.

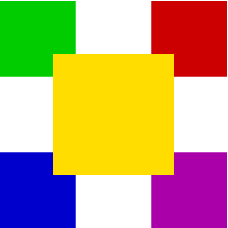

This example uses 'z-index' and negative margins to make the

element in the middle slot partly overlap the elements in the other

slots:

body { display: "a.b"

".c."

"d.e";

height: 6cm;

width: 6cm }

#a { background: #0C0; position: a }

#b { background: #C00; position: b }

#c { background: #FD0; position: c; margin: -1em; z-index: 1 }

#d { background: #00C; position: d }

#e { background: #A0A; position: e }

3.9. Floating elements inside

templates

An element may be positioned inside a template (computed value of '<letter>' for

its 'position'

property) and be a floating element at the same time (computed value of

its 'float' property is

other than 'none'). The following cases must be

distinguished:

- Page-based floats – In paged media (see [CSS3PAGE]), if the value of 'float' specifies that the

element floats to the top or bottom of the page (in a horizontal writing

mode) or the left or right of the page (in a vertical writing mode), the

'position' property

doesn't apply.

- Normal floats – In other cases, the element floats normally

within its containing block, which in this case is its slot in the

template (as defined above).

3.10. Possible other approaches

The template approach is easy and avoids introducing @-rules and extra

properties, but it is also limited: no way to add borders or backgrounds

to the template.

A more flexible approach would be to define templates as @-rules, in the

same manner that page layouts are defined with @page rules. Such an

approach might look like this:

@template form1 {

@row {}

@row {

@slot {}

@slot {colspan: 4}

@slot {}

@slot {colspan: 4}

@slot {}

}

@row {}

@row {

@slot {}

@slot {colspan: 4}

@slot {}

@slot {colspan: 4}

@slot {}

}

@row {}

@row {

@slot {colspan: 4}

@slot {colspan: 2}

@slot {colspan: 2}

@slot {colspan: 2}

}

@row {}

}

Instead of specifying the layout in CSS, one could also use a third

file, possibly in XML, e.g.:

body {template: url(panes.xml)}

where “panes.xml” looks like this:

<?xml-stylesheet href="panes.css"?>

<template>

<row>

<main rowspan="2" colspan="2"/>

<side1/>

<side2/>

</row>

<row>

<bottom rowspan="2"/>

</row>

<template>

The above template is equivalent to (main=a, side1=b, side2=c,

bottom=d):

display: "aabc"

"aadd"

The extra indirection allows the template to have a style sheet of its

own.

Yet another approach is XBL, but that requires XML and additional

downloads. XBL also has elements relating to events and scripts, that are

not needed for layout.

4. Tabbed (stacked) displays

| Name:

| tab-side

|

| Value:

| top | bottom | left | right

|

| Initial:

| top

|

| Applies to:

| elements with 'display: stack'

|

| Inherited:

| yes

|

| Percentages:

| n/a

|

| Media:

| visual

|

| Computed Value:

| specified value

|

An element with a 'display-model' of 'stack' displays only one of its children, all of which

have a role of 'card'. (Elements may be wrapped in

anonymous boxes to ensure this, see below.)

The user can interactively change which child is shown. Initially, the

first child is visible (but see “fragment

IDs” below). In non-interactive, visual media, which child is

visible is undefined. Descendants with a role of 'tab' are shown along the top (or side) of the stack.

An interactive UA should allow the user to select a card to show by

selecting (clicking, etc.) the associated

tab.. A UA may also allow users to select cards that don't have a

tab, but this is not required.

The following document displays three tabs corresponding to three

cards. The user can select the card to show:

<style type="text/css">

body {background: silver; color: black}

div.records {display: stack; border: outset}

div.record {display: card}

h2 {display: tab; width: 5em; border: outset; text-align: center}

h2:current {border-bottom: solid silver}

</style>

<div class=records>

<div class=record>

<h2>Men's fashion</h2>

<ul>

<li>Oversized jeans, 4 pockets.

<li>…

<ul>

</div>

<div class=record>

<h2>Women's fashion</h2>

…

</div>

<div class=record>

<h2>Children's fashion</h2>

…

</div>

</div>

The result might look like this:

''display: stack'' is a shorthand for a role of 'block' and a model of 'stack'.

'display: card' is a shorthand for a role of 'card' and a model of 'block-inside'. 'display: tab' is

a shorthand for a role of 'tab' and a model of

'block-inside'.

An element with a model of 'stack' has two parts,

that are layed out as two (anonymous) boxes with roles of 'block' inside a box with a model of 'block-inside'. The first part has a model of 'inline-inside', the second a model of 'block-inside'. The second part establishes a stacking context [def'd where in

CSS3?] and a block formatting

context [def'd where in CSS3?] for the element's descendants.

The second part has a width and height equal to the maximum width and

height over all the element's children (real or anonymous) with a role of

'card'. It is also the containing block

for these children (of which only one is displayed at any time).

All associated tab elements are

flowed into the first part, as if they had a role of 'inline'. Their order is the same as the document order.

They are thus taken out of the flow of their parent.

One variant of a tabbed display may be where not the labels

of the contents are shown, but only buttons to go forward and backward.

This style is sometimes referred to as a “wizard” interface.

Maybe select it with 'display: cards'.

4.1. Anonymous card and

stack boxes

If any child of an element with a model of 'stack' has a role other than 'none' or 'card', that child is

wrapped in an anonymous box with a

role of 'card'. The other properties of the

anonymous box are inherited or have their initial values.

If any sequence of one or more sibling elements with roles of 'card' or 'none' has a parent with

a model other than 'stack', an anonymous box is

wrapped around the sequence. The sequence must begin and end with a 'card' element. The anonymous box has a model of 'stack'. The other properties of the anonymous box are

inherited or have their initial values.

Although the following document fragment has no explicit stack element,

the section elements are still displayed as a stack, because an anonymous

stack box is automatically created.

<style type="text/css">

section {display: card}

h {display: tab}

</style>

<section>

<h>Introduction</h>

<p>…</p>

</section>

<section>

<h>Quick start</h>

<p>…</p>

</section>

…

4.2. Tab elements

A tab element is the associated tab of its

nearest ancestor of type card, if it is the first tab inside that card (in

document source order). An associated tab element has a computed value for

'display-role' of 'tab'. If the tab element is not associated with any

card, its computed value is 'inline'.

Note that the 'appearance' property also has a value 'tab'. The two can be used together (''display: tab;

appearance: tab''), to ensure that an element that functions as a tab

looks like a platform-native tab. The two properties are independent,

however, and can be used on their own.

Note also that the Borders and Backgrounds

module [CSS3BG] allows more control over the

look of the borders and backgrounds.

4.3. Relation of position, float,

tab and card

If an element has a computed 'position' of 'fixed',

'absolute' or '<letter>', then a

specified 'display-role' of 'tab' or 'card' results in a

computed value of 'block'.

If an element has a computed value for 'display-role' of 'card' or

'tab', the 'float' property does not apply and its computed

value is 'none'.

4.4. :Active and :current tabs

A tab element matches the ':active' pseudo-class while a user activates the element

to make the associated card visible. This is typically a transient state,

which lasts as long as the user holds a mouse button pressed over the

element or presses some other key.

A tab element matches the ':current' pseudo-class if it is the associated tab of the currently visible card

element.

h2 {display: tab; background: silver}

h2:current {background: white}

h2:active {color: red}

4.5. Borders, padding and stacking

order within a stack

The border and padding of a stack element are only drawn around its

second part, not around the box with the tabs. Furthermore, at the

boundary between the first and second part, the border is not drawn

between the parts, but overlapping the first part. More precisely: the

border edge of the first part (which is the same as its padding and

content edge) touches the padding edge of the second box.

The stacking order inside a stack element is from

bottom (away from the user) to top (closest to the user):

- All tab elements in document order, except for the one

':current' tab.

- The backgound and border of the stack element.

- The currently visible card element.

- The

':current' tab.

The border of the stack is thus in front of all tabs, except the one

matching ':current'.

The border of the stack where it overlaps the element's first part is

clipped to the height of that part. The border will not extend outside the

stack element.

4.6. Dynamic reordering of tabs

Some platforms render platform-native tabbed dialog boxes with many tabs

in such a way, that the current default tab is always on the last line,

directly adjacent to the card. They reorder

the tabs if needed. UAs running on such platforms may reorder tabs

in this way. However, for usability reasons, tab reordering is not

recommended.

Also for usability reasons, we recommend that designers limit the number

of cards and tabs so that all tabs fit on one line.

4.7. Fragment IDs

UAs should attempt to make elements visible that match the ':target' pseudo-class. (Typically, this is an element

with an ID equal to the fragment ID at the end of the URL of the page, see

Selectors [SELECT].) If such an element is a

card element, or inside a card element, the UA should make that card

element the initially visible card of the stack.

Note that this provides an alternative way for users to

select a card to show: if the UA supports hyperlinking and if each card

(or at least some element inside the card) has an ID, activiating a link

to that ID makes that card the default. (But often, it also scrolls the

page, so that the stack is at the top of the window, which may be an

undesired side-effect.)

5. Row and column layouts

This is an alternative to the layout policy above. Probably

we don't need both. Maybe the best parts can be combined: layout that is

independent from the document structure in one case and arbitrary levels

of stretchability in the other.

| Name:

| box-orient

|

| Value:

| horizontal | vertical | inline-axis | block-axis

|

| Initial:

| inline-axis

|

| Applies to:

| box elements

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| n/a

|

| Media:

| visual

|

| Computed Value:

| specified value

|

| Name:

| box-direction

|

| Value:

| normal | reverse

|

| Initial:

| normal

|

| Applies to:

| box elements

|

| Inherited:

| yes

|

| Percentages:

| n/a

|

| Media:

| visual

|

| Computed Value:

| specified value

|

To make this document fragment:

<box>

<button>Child 1</button>

<button>Child 2</button>

<button>Child 3</button>

</box>

look like a row of buttons at their intrinsic size, you could use this

rule:

box {display: box}

(and properties to give the buttons the proper border.)

With templates, it would be like this:

box {display: "abc"}

button {position: a}

button + button {position: b}

button + button + button {position: c}

To make two buttons in a row and give each a specific size, it is

enough to add a width:

<box>

<button style="width: 200px">Child 1</button>

<button style="width: 100px">Child 2</button>

</box>

| Name:

| box-sizing

|

| Value:

| content-box | padding-box | border-box | margin-box

|

| Initial:

| content-box

|

| Applies to:

| box and block elements

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| n/a

|

| Media:

| visual

|

| Computed Value:

| specified value

|

| Name:

| box-align

|

| Value:

| start | end | center | baseline | stretch

|

| Initial:

| stretch

|

| Applies to:

| box elements

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| n/a

|

| Media:

| visual

|

| Computed Value:

| specified value

|

| Name:

| box-flex

|

| Value:

| <number>

|

| Initial:

| 0.0

|

| Applies to:

| children of box elements

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| n/a

|

| Media:

| visual

|

| Computed Value:

| specified value

|

| Name:

| box-pack

|

| Value:

| start | end | center | justify

|

| Initial:

| start

|

| Applies to:

| box elements

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| n/a

|

| Media:

| visual

|

| Computed Value:

| specified value

|

Assume again this mark-up:

<box>

<button>Child 1</button>

<button>Child 2</button>

<button>Child 3</button>

</box>

To make the three buttons appear clustered in the center of the row:

box {display: box; box-pack: center}

Or, with a template that includes whitespace before and after the row

and marks it as flexible:

box {display: ".abc." * intrinsic intrinsic intrinsic *}

button {position: a}

button + button {position: b}

button + button + button {position: c}

To align them to the right:

box {display: box; box-pack: end}

Or, with a template that includes whitespace after the row and marks it

as flexible:

box {display: "abc." intrinsic intrinsic intrinsic *}

button {position: a}

button + button {position: b}

button + button + button {position: c}

To align the first one to the left and the other two to the right:

box {display: "a.bc" intrinsic * intrinsic intrinsic}

With 'box-flex',

you can make boxes that grow at different speeds:

<box>

<button id=b1>Cat</button>

<button id=b2>Piranha</button>

<button id=b3>Canary</button>

</box>

with style:

box {display: box; box-orient: vertical}

#b1 {box-flex: 1}

#b2 {box-flex: 2}

#b3 {box-flex: 3}

Without an explicit height for the BOX, there will be a stack of three

buttons with the same height. But when the height is set to larger and

larger values, the heights of the buttons will approach 1/6, 1/3 and 1/2

of the BOX's height, respectively. This cannot be done with templates.

On the other hand, with a template like this:

box {display: "a *"

". "

"b *"

"b *"

". "

"c *"

"c *"

"c *"}

#b1 {position: a}

#b2 {position: b}

#b3 {position: c}

The second button will always be twice the height of the first and the

third button three times. This cannot be done with 'box-flex'.

| Name:

| box-flex-group

|

| Value:

| <integer>

|

| Initial:

| 1

|

| Applies to:

| children of box elements

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| n/a

|

| Media:

| visual

|

| Computed Value:

| specified value

|

| Name:

| box-lines

|

| Value:

| single | multiple

|

| Initial:

| single

|

| Applies to:

| box elements

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| n/a

|

| Media:

| visual

|

| Computed Value:

| specified value

|

6. Profiles & UA conformance

[…]

7. CR exit criteria

[…]

8. History

(This section is not normative.)

The following types of use cases were considered for

template-based layout. Not all of them may be possible with CSS

level 3.

-

Standard Web pages.

-

Grids and other table-like layouts. This includes Grid layouts, Frame

layouts and table-like subdivision of a rectangular area.

-

A layout structure with “flex”ing information. The flexing

is represented by constraints that specify how the cells are to relate

to one another. Which cells are to be allowed to grow or shrink and how

much. There may also be a priority ordering, which determines, based on

the size of the allowed display window, which cells shrink, which grow

and under which conditions.

-

Layout structures with absolutely positioned (fixed-size) elements;

for example a block of text into which several illustrations intrude at

fixed positions within the block. This is like a float with respect to

tightly wrapping the text around the intrusion, but the position of the

intrusion is determined by the layout structure, not the content flowed

into that structure.

An example of this is a multi-column layout with one or more

absolutely positioned “floats” that intrude on the columns:

[make graphic]

+-------------------------------+

| +-Cell-0---------+ |

| | | |

| | | |

| +----------------+ |

| |

| +-Cell-s1---+ +-Cell-2----+ |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | *Intrusion** | |

| | * | | * | |

| | * | | * | |

| | * | | * | |

| | ************ | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| +-----------+ +-----------+ |

| |

+-------------------------------+

Here there are three cells: Cell-0, Cell-1 and Cell-2 and one

intrusion, Intrusion. Cell-0 would be filled by a heading, Cells -1 and

-2 would be columns that would be filled by a two column story and the

Intrusion could be filled by a “pull quote” from the story

or a graphic that illustrates the story. The two columns would

“wrap around” the Intrusion.

-

Multiple, disconnected, fixed-size areas on a page that are chained

together, each one receiving the content that doesn't fit in the

previous slot. In combination with page breaks, this may give the layout

of some newspaper: the first few lines of each story on the first page,

the rest of the story in other areas on subsequent pages. (It will

probably need a way to conditionally insert “continued on

page 7” or similar text.)

For comparing proposals for template-based layouts, the working group

identified four important aspects of each proposal:

-

the physical layout structures – the way of structuring the

“cells” (slots) into which content is flowed. This includes

a way to identify the various layout containers.

-

the binding mechanism – the way to specify that a given element

(and its descendants) are to be placed in a given layout cell.

-

the property distribution mechanism – the way to put properties

onto the layout structure and the cells within it.

-

the flexing mechanism – the way to describe how the layout

structure should adapt itself to the higher level container (window) in

which it is placed. This includes statements about which cells should

grow and when they should grow.

In the first proposal above, which specifies the template inside the

'display' property,

these aspects are as follows:

-

A character matrix is used to show the layout structure and the cells

are named by the character used to show where they are positioned.

-

The binding of content to cells is handled by the 'position' property which

identifies a cell to which the content is bound.

-

It is difficult to attach properties to the layout structure. Only the

shape, size and flexibility of the layout are specified explicitly. Some

properties (background, border and vertical alignment) are attached

indirectly, by attaching them to the element that occupies a slot.

-

There is no “flexing” information, in the sense of some

slots being more flexible than others. The choice is between fixed size,

a fraction of the available size or the content's intrinsic size. (The

latter is further subject to min/max sizes specified on that content.)

It is not possible to say, e.g., that some column can only become wider

if all other columns are at their maximum size.

Acknowledgments

[acknowledgments]

Based on ideas by

Dave Raggett [member-only link],

Ian Hickson [member-only link], Håkon Lie and Bert Bos.

References

Normative references

-

- [CSS3SYN]

- L. David Baron. CSS3 module: Syntax. 13 August 2003. W3C

Working Draft. (Work in progress.) URL: http://www.w3.org/TR/2003/WD-css3-syntax-20030813

- [CSS3VAL]

- Håkon Wium Lie; Chris Lilley. CSS3 module: Values and

Units. 13 July 2001. W3C Working Draft. (Work in progress.) URL:

http://www.w3.org/TR/2001/WD-css3-values-20010713

- [UNICODE]

- The Unicode Consortium. The Unicode Standard. 2003.

Defined by: The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 (Boston, MA,

Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-321-18578-1), as updated from time to time by the

publication of new versions URL: http://www.unicode.org/unicode/standard/versions/enumeratedversions.html

Other references

-

- [CSS3BG]

- Tim Boland; Bert Bos. CSS3 module: Backgrounds. 2 August

2002. W3C Working Draft. (Work in progress.) URL: http://www.w3.org/TR/2002/WD-css3-background-20020802

- [CSS3BOX]

- Bert Bos. CSS3 module: The box model. 24 October 2002.

W3C Working Draft. (Work in progress.) URL: http://www.w3.org/TR/2002/WD-css3-box-20021024

- [CSS3PAGE]

- Håkon Wium Lie; Jim Bigelow. CSS3 Paged Media

Module. 25 February 2004. W3C Candidate Recommendation. (Work in

progress.) URL: http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/CR-css3-page-20040225

- [CSS3POS]

- Bert Bos. CSS3 Positioning Module. (forthcoming). W3C

Working Draft. (Work in progress.)

- [CSS3TEXT]

- Michel Suignard. CSS3 Text Module. 14 May 2003. W3C

Candidate Recommendation. (Work in progress.) URL: http://www.w3.org/TR/2003/CR-css3-text-20030514

- [CSS3UI]

- Tantek Çelik. CSS3 Basic User Interface Module. 3

July 2003. W3C Working Draft. (Work in progress.) URL: http://www.w3.org/TR/2003/WD-css3-ui-20030703

- [MEDIAQ]

- Håkon Wium Lie; Tantek Çelik; Daniel Glazman. Media

Queries. 8 July 2002. W3C Candidate Recommendation. (Work in

progress.) URL: http://www.w3.org/TR/2002/CR-css3-mediaqueries-20020708

- [SELECT]

- Daniel Glazman; et al. Selectors. 13 November 2001. W3C

Candidate Recommendation. (Work in progress.) URL: http://www.w3.org/TR/2001/CR-css3-selectors-20011113

Index

- ':active', #

- anonymous, #

- appearance, #

- associated tab, #

- box-align, #

- box-direction, #

- box-flex, #

- box-flex-group, #

- box-lines, #

- box-orient, #

- box-pack, #

- box-sizing, #

- ':current', #

- direction, #

- display, #

- display-model, #

- float, #

- height, #

- layout algorithm, #

- <letter>, #

- maximum intrinsic width, #

- minimum intrinsic width, #

- overflow, #

- page-break-before, #

- position, #

- reorder the tabs, #

- slot, #

- stacking order, #

- tab-side, #

- target width, #

- template ancestor, #

- template element., #

- <col-width>, #

- <row-height>, #

- width, #

- writing-mode, #

- z-index, #

Property index

| Property

| Values

| Initial

| Applies to

| Inh.

| Percentages

| Media

|

| box-align

| start | end | center | baseline | stretch

| stretch

| box elements

| no

| n/a

| visual

|

| box-direction

| normal | reverse

| normal

| box elements

| yes

| n/a

| visual

|

| box-flex

| <number>

| 0.0

| children of box elements

| no

| n/a

| visual

|

| box-flex-group

| <integer>

| 1

| children of box elements

| no

| n/a

| visual

|

| box-lines

| single | multiple

| single

| box elements

| no

| n/a

| visual

|

| box-orient

| horizontal | vertical | inline-axis | block-axis

| inline-axis

| box elements

| no

| n/a

| visual

|

| box-pack

| start | end | center | justify

| start

| box elements

| no

| n/a

| visual

|

| box-sizing

| content-box | padding-box | border-box | margin-box

| content-box

| box and block elements

| no

| n/a

| visual

|

| position

| <letter> | same

| N/A

| '<letter>' or 'static'; see text

|

| tab-side

| top | bottom | left | right

| top

| elements with 'display: stack'

| yes

| n/a

| visual

|

The following properties are defined elsewhere:

![[rendering of three tabs]](tab1.png)